Why Oil Companies Want California’s Water — All Fracked Up! Big Oil Fracking Our Environment— Fracking: Oil Shale Oil, Water and Politicians Do Mix:The Politicians, the Corporate Media and Their Subservience To Big Oil Are Fracking Up California’s Water Resources.

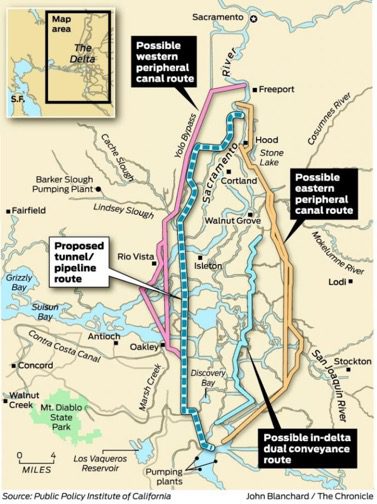

San Francisco Chronicle Healdine: New state water plan: tunnels under delta

San Francisco Chronicle Healdine: New state water plan: tunnels under delta

Today, I read, this above article in today’s San Francisco Chronicle with contempt for the corporate media and their politicians.

With the new water bill, that is now being proposed by the big oil and energy and the political support by thier politicians (like Diane Feinstein etc., proposing the old defeated Peripheral Canal proposal. I think that we have a golden opportunity to unite everyone into the fight.

Most people don’t know that the big energy companies control most of the water in the

San Joaquin Valley. Now, with fracking profitable in California due to the high price of fuel, they want to frack California and our water resources required by the fracking process. (As they are trying to do in the rest of the country.)

At the peak of California production in 1985, Kern County producers needed roughly four-and-a-half barrels of water to produce a single barrel of oil.

Today, that ratio has jumped to almost eight barrels of water per barrel of oil. This use has been sanctioned despite the three-year drought that has ravaged the valley, causing reductions in the water delivered by the State and Central Valley projects canals. Not only are farmers generally short of water, dozens of small poor agricultural hamlets — including Alpaugh, Seville, East Orosi and Kettleman City — have been forced to tap groundwater. And that groundwater is often contaminated with agricultural pollutants, including arsenic and nitrates. — Oil and Water Don’t Mix with California Agriculture

Shale is found in about one sixth of California. “The Monterey shale overlaps much of California’s traditional crude producing regions. It generally runs in two swaths: a roughly 50-mile wide ribbon running length of the San Joaquin Valley and coastal hills, and a Pacific Coast strip of similar width between Santa Barbara and Orange County.” —A Big Shale Play in California Could Boost the Golden State’s Oil Patch

This need for more water, at the same time that the big energy companies have already sucking dry the Colorado water basin, at a time of drought in the southwest.

(“The group, Western Resource Advocates, used public records to conclude that energy companies are collectively entitled to divert more than 6.5 billion gallons of water a day during peak river flows. The companies also hold rights to store, in dozens of reservoirs, 1.7 million acre feet of water, enough to supply metro Denver for six years.” — Oil, Water Are Volatile Mix in West, Energy Firms Buying River Rights Add to Competition for Scarce Resource)

As fresh drinking water is depleted due to fracking, the Delta, San Francisco Bay, etc., will become even more polluted.

Farmworkers and small farmers will have less safe drinking water, as the valley water table gets more polluted by the fracking process.

In, addition fackin has been associated with earthquakes. ( Read Arkansas ‘Fracking’ Site Closures Extended As Earthquake Link Studied)

There have been world wide struggles against the privatisation of water just as there have been war in the middle east for control and production of war. These wars are now coming home.

With the recession/depression we will soon not be able to drink and eat unpolluted water and food. A basic ‘unalienable rights to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness’.

I think that all of these issues are now clear enough to begin to unite all, fight for, and win a better world.

Oil and Water Don’t Mix with California Agriculture By Jeremy Miller

At the peak of California production in 1985, Kern County producers needed roughly four-and-a-half barrels of water to produce a single barrel of oil. Today, that ratio has jumped to almost eight barrels of water per barrel of oil. This use has been sanctioned despite the three-year drought that has ravaged the valley, causing reductions in the water delivered by the State and Central Valley projects canals. Not only are farmers generally short of water, dozens of small poor agricultural hamlets — including Alpaugh, Seville, East Orosi and Kettleman City — have been forced to tap groundwater. And that groundwater is often contaminated with agricultural pollutants, including arsenic and nitrates.

KERN COUNTY, CALIFORNIA

From the “Petroleum Highway” — a rutted, dusty stretch of California State Route 33 — you can see the jostling armies of two giant industries. To the east, relentless rows of almonds and pistachios march to the horizon. To the west, an armada of oil wells sweeps to the foothills of the Temblor Range.

Fred Starrh, who farms along this industrial front, has seen firsthand what can happen when agriculture collides with oil. On an overcast February day, he drives his mother-of-pearl Lincoln Town Car down a dirt road through his orchards. Starrh Farms has 6,000 acres of pistachios, cotton, almonds and alfalfa. Starrh proudly points out almond trees planted 155 to the acre with the aid of lasers and GPS. At the edge of his land, he pulls up beside 20-foot-high earthen berms, the ramparts of large “percolation” ponds that belong to a neighbor, Aera Energy.

From the mid-1970s to the early 2000s, Aera dumped more than 2.4 billion barrels (or just over 100 billion gallons) of wastewater — known in the industry as “produced water” — from its North Belridge oilfield into those unlined ponds, Starrh says. The impact became apparent beginning in 1999, when Starrh dug several wells to augment the irrigation water he gets from the California Aqueduct. He mixed the groundwater with aqueduct water, applied it to a cotton field beside the berms — and the plants wilted. Eventually, the well water killed almond trees, Starrh says; he points out a few that look like gray skeletons.

Starrh suspected that Aera’s ponds were leaking pollutants. So he tested his well water and found high concentrations of chloride and boron along with detectable radiation — common constituents of the oil industry’s produced water. He took Aera — a joint venture of Shell and ExxonMobil — to court, and in the nine years of legal wrangling that followed, Aera was forced to disclose its practices. The state’s regional water-quality control board ordered the company to stop dumping into the ponds, and Aera launched a cleanup of the site. Last January, a Kern County jury awarded Starrh $8.5 million in damages and by October, the ponds had been demolished. But Starrh has appealed that court decision, saying he’ll need as much as $2 billion to rehabilitate his land and construct terraced ponds to “flush” his soil and groundwater of toxins.

The oil company should be “punished,” says Starrh. “If you just hit them with a small fine, it becomes just a small expense of doing business.”

Many local farmers face the same risk, Starrh believes. Kern County belies the old adage: Out here, oil and water do mix — and they do so in staggering volumes. Moreover, Kern County’s oilfields are a preview of the future of oil worldwide. The industry is moving further into the realm of “unconventional” fuels — including tar sands, shale oil and “heavy oil,” like the oil found here. But heavy oil requires the use and disposal of huge amounts of water. And the consequences are strewn across the local landscape.

Kern County’s oilfields, which began producing in the mid-1800s, helped build the Standard Oil empire that eventually evolved into the likes of Chevron and ExxonMobil. The local Lakeview Gusher of 1910 remains California’s greatest single strike and one of the largest oil spills in U.S. history; an estimated 9 million barrels spewed uncontrollably from it, creating a lake of oil.

The local oil is “heavy” due to its geology (shallow deposits and tectonic movement) and biochemistry (petroleum-consuming bacteria living near the surface have made the crude the consistency of molasses). In the early days, companies skimmed off the lighter portions of the oil. Over the years, they developed methods to extract the heavier stuff, overcoming the oil’s resistance to flow by injecting water and superheated steam underground. These extraction techniques, known as “waterflooding” and “steamflooding,” loosen up the oil and push the tar toward closely spaced well bores, from which it is siphoned to the surface by pumps.

Despite their age, Kern County’s oilfields still produce about 8 percent of the nation’s domestic supply. Tens of thousands of pump jacks stand shoulder to shoulder amid a rusting circulatory system of pipelines. The hillsides glow with flares of natural gas venting from oil wells. And dozens of gas-fired steam generators and cogeneration power plants represent the oil industry’s up-front water consumption. They supply steam to the oilfields through ubiquitous silver pipes.

Since the 1960s, when steamflooding was pioneered in Kern County, California oil companies have pumped more than 2.8 trillion gallons of freshwater into the ground — an annual average large enough to supply a city of one million people. Some of that water is the industry’s own recycled wastewater and some is bought from irrigation districts. A large portion of that water use occurs here, and the complicated plumbing is not easily untangled.

Oil companies must report the overall amount of water they inject into the ground to the agency overseeing oil production — the California Division of Oil, Gas and Geothermal Resources. Though they don’t say much about it, they get a great deal of this water from California’s overburdened irrigation system — in this case, the State and Central Valley water projects, which use dams and long-distance canals to divert river water to farms and other customers. According to J.D. Bramlet, superintendent of the West Kern Water District, which distributes water from the State Water Project to the west side of the San Joaquin Valley, oil companies and steam-producing cogeneration plants (most of which are owned by the oil companies) received 83 percent of the district’s 31,500 acre-foot allocation in 2009. That means that last year, oil companies doing business with this single water district took roughly 8.4 billion gallons of water, the bulk of which they use to push heavy oil to the surface.

And year by year, it takes more freshwater to extract the oil that remains. At the peak of California production in 1985, Kern County producers needed roughly four-and-a-half barrels of water to produce a single barrel of oil. Today, that ratio has jumped to almost eight barrels of water per barrel of oil.

This use has been sanctioned despite the three-year drought that has ravaged the valley, causing reductions in the water delivered by the State and Central Valley projects’ canals. Not only are farmers generally short of water, dozens of small poor agricultural hamlets — including Alpaugh, Seville, East Orosi and Kettleman City — have been forced to tap groundwater. And that groundwater is often contaminated with agricultural pollutants, including arsenic and nitrates.

Even as the local oil industry uses a lot of irrigation water, it generates an even larger outflow of contaminated “produced water” — the stuff that poisoned Fred Starrh’s crops. This includes some water that returns to the surface after it’s been injected into the ground, but much of the outflow is simply a consequence of producing oil from an aging oilfield. Groundwater migrates into the pore spaces of oil-bearing formations as the oil is sucked away, and over time, the companies must pump up more and more water to get the remaining oil.

Much of the “produced water” in the west-side oilfields of Kern County contains naturally occurring heavy metals and other inorganic compounds associated with the oil. Until the 1980s and 1990s, the area’s “produced water” was managed very loosely. Jan Gillespie, a geology professor at California State University-Bakersfield, recalls that when she worked for a local oil company in the late ‘80s, the produced water was merely shunted into ephemeral creeks. Any oily fluid that wasn’t absorbed into the creek beds would eventually arrive at a pond. “Every so often, a big tar mat would build up on the bottom (of a pond) and the water wouldn’t seep in anymore. So someone would toss a stick of dynamite and blow up the mat, and things would start to percolate again.”

Oil companies insist that produced water is mostly harmless — and federal law appears to agree. In 1988, during the Reagan administration, the Environmental Protection Agency classified crude oil and produced water as “special wastes” rather than “hazardous substances,” exempting them from the stringent requirements of the main law for tracking toxic substances, the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act. Several EPA whistleblowers later came forward, pointing out that crude oil and its produced waters are often laden with individual substances considered “hazardous” under the federal law. “This was the first time in the history of environmental regulation of hazardous wastes that the EPA has exempted a powerful industry for solely political reasons, despite a scientific determination of the hazardousness of the wastes,” Hugh Kaufman, a former EPA ombudsman, told the Associated Press in 1988.

Kern County’s fields now cough up roughly nine barrels of produced water for every barrel of tarry oil. Year by year, the ratio becomes more skewed toward produced water. In 2007, Kern County oilfields generated 1.3 billion barrels of produced water for 166 million barrels of oil. In 2008, the produced water increased by 100 million barrels, while oil production fell by 3 million barrels.

Produced water is usually disposed of by being piped to surface evaporation ponds or to injection wells. The California Regional Water Quality Control Board oversees all discharges to the surface, including evaporation ponds. Produced water injected into disposal wells is monitored jointly by the EPA and the California Division of Oil, Gas and Geothermal Resources. These layers of oversight also have a spotty record.

Some of the tainted water is cleaned and sent to the cogeneration plants, where it is converted to steam. The “purest” of the water is only lightly treated and may be applied directly to crops. One place this happens is at Chevron’s Kern River oilfield near Bakersfield, which the company often cites as evidence of the compatibility of oil production and agriculture. The produced water at Kern River is said to be quite “fresh” — reportedly the result of infiltration of runoff from the Sierra mountain range — with low concentrations of hydrocarbons, boron, salt and heavy metals. Since 1994, the company has lightly treated the water and sold it to farmers, garnering much attention in the engineering world and an award from the California Water Resources Control Board.

On the other hand, at Chevron’s Lost Hills oilfield, 30 miles northwest of Kern River, the company pumped millions of barrels of produced water laced with heavy doses of boron into unlined evaporation pits each year. The pits were adjacent to croplands and, according to Chevron records, 3,500 feet from the California Aqueduct. That practice ceased in 2008, under pressure from the regional water board.

Tupper Hull, a spokesman for the Western States Petroleum Association, says that oil companies recycle a significant portion of their wastewater, and adds that it’s in their financial interest to do so. Chevron spokesman Jim Waldron says the company recycles up to 90 percent, although Chevron refuses to explain how it achieves that rate. Hull says companies tend to consider the details “proprietary — oil companies are competing with one another. It’s not in their best interest to disclose their methods.”

But there is strong financial incentive for companies merely to dispose of produced water. According to Matt Trask, a California energy analyst, cleaning the produced water can cost up to three to five times as much as buying water on the open market — and sometimes 10 times as much. Thus, in Kern County in 2008, according to state statistics, oil companies pumped 425 million barrels of produced water into underground disposal wells and discarded 200 million barrels into surface evaporation ponds. That amounts to nearly half of the local produced water.

Evaporation ponds and sumps are being gradually eliminated. But Clay Rodgers, an officer with the California Regional Water Quality Control Board’s Fresno division, estimates that there are still hundreds of pond “sites” — containing more than 1,000 individual ponds and sumps — across Kern County. And none of the ponds receiving oil wastes in Kern County are lined, Rodgers says. From a Google Earth-vantage, one can see these potentially hazardous manmade lakes, often arrayed in rows of four or five. Some ponds occupy a few hundred square feet; others are as large as several acres. Some are dry or hold just a small amount of residual water, but others are brimming with fluid.

The wastewater ponds not only threaten to pollute both surface and groundwater, they also might be dangerous to the health of wildlife and people. But little is known about the health risks. Matt Constantine, the director of the Kern County Environmental Health Services Department, says his agency focuses on produced water only when “there is a referral from the water board or a complaint from the public.”

Constantine’s agency did clamp down on one huge produced-water disposal site west of Bakersfield, operated by Hondo Chemical, after problems there — including fires — got out of control. To get an idea of the problem’s scale, he flew a chartered helicopter over the site. In his office last October, he pulls out a thick binder filled with aerial photos, showing several large evaporation ponds, their surfaces various shades of green, blue and black from oil residues. “It is just an absolute mess,” says Constantine as he flips through the pages.

The Hondo Chemical site is perched atop the Kern Water Bank, an underground reservoir that supplies water to municipal and agricultural users throughout the valley. “That presents a very significant concern,” Constantine says. In 2007, his agency ordered Hondo to cease operations. The Kern County Board of Supervisors has since found Hondo to be in violation of environmental and health regulations and ordered the company to begin remediation. But Constantine says the cleanup is going slowly.

The serious interest in Kern County’s heavy oil is emblematic of global changes. With worldwide stocks of the best raw oil — “light sweet crude” — dwindling, heavy oil and other “unconventional” fuels are now estimated to hold 80 percent of the remaining petroleum reserves. That’s why major oil companies are going for Canada’s Athabascan tar sands and the heavy oil deposits of Venezuela’s Orinoco and Mexico’s Cantarell and Ku-Maloob-Zaap fields.

These once-maligned fuel precursors are the subject of giddy discussion in corporate boardrooms and R&D departments. Alberta’s tar sands have recently become this country’s leading foreign source of crude oil, surpassing imports from Saudi Arabia. “If the heavy oil and bitumen (or natural asphalt) deposits in the U.S. and Canada are brought to market,” says a Houston-based consulting firm, Petroleum Equities Inc., “they would alone satisfy the current demand for oil in both countries for more than 150 years.”

But this “unconventional” petroleum carries a host of heightened impacts. The production and refining of a barrel of oil from Alberta’s tar sands generates two to three times the amount of carbon emissions as a barrel of conventional crude. Those tar sands operations also generate wastewater ponds similar to the ones in Kern County. Syncrude Canada, a leading producer of tar sands oil, was found guilty in a Canadian court earlier this year of causing the deaths of 1,600 ducks.

Many people don’t realize the risks and costs of the oil industry’s new direction. In Kern County, Chevron announced in 2008 that it plans to invest nearly $1 billion in the production from its local heavy-oil fields. Meanwhile, produced water generated by various companies can even be found in reeking ponds adjacent to — and within — the city of Taft, a hardscrabble, historic oil town atop the Midway-Sunset oilfield. Town streets are named after General Petroleum and Chevron. Near a church, a trickle of oily outflow from one small pond sometimes reaches a dry streambed.

Such problems are seldom covered by local media, including the region’s largest newspaper, the Bakersfield Californian, and the biweekly Taft Midway Driller. The Driller’s editor, Doug Keeler, says, “If you’re a business owner in Taft, you are beholden, either directly or indirectly, to the oil industry. … We did (a story) three, four, maybe five years ago on a company that was putting water down a well that caused contamination. In newspaper time, that’s a really long time (ago).”

Even the local Sierra Club chapter hesitates to delve too deeply into the affairs of the petroleum industry. Lorraine Unger, treasurer and spokeswoman for the group’s Kern-Kaweah Chapter, lives in Bakersfield, in an area known as “The Bluff,” which has a panoramic view of the Kern River oilfield. Many members of her Sierra Club chapter work for oil companies, and Chevron, she says, is “not so bad, as far as oil companies go.”

Unger knows a fair amount about produced water. “They used to run it right through the agricultural ditches,” she recalls. “I can see it all from my backyard.” But she says her chapter is not terribly concerned about the practice. After all, there are plenty of other local issues to worry about — air pollution, sprawl, and the poaching of black bears in the Sierra foothills.

“Besides, even if I was concerned about the water, oil is just too big and powerful around here to go after,” Unger says. “It puts food on people’s tables.”

This story was made possible with support from the Kenney Brothers Foundation.

OPEN FORUM On Energy — A fracking mess By Peter Gleick and Heather Cooley

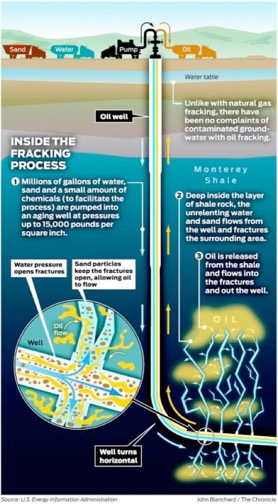

Efforts to expand natural gas production through “hydraulic fracturing” or “hydrofracking” are raising tensions across the country. Fracking releases natural gas trapped in underground shale formations by injecting water, chemicals and sand to fracture the rock and release the gas.

Efforts to expand natural gas production through “hydraulic fracturing” or “hydrofracking” are raising tensions across the country. Fracking releases natural gas trapped in underground shale formations by injecting water, chemicals and sand to fracture the rock and release the gas.

Twenty years ago, unconventional gas produced from shales, coal-bed methane and similar formations made up 10 percent of total U.S. gas production. Today it is around 40 percent and growing rapidly along with controversy over the possible environmental impact of hydrofackinging.

Pundits and fracking proponents argue that stronger regulations are unnecessary to protect the public or that opposition to uncontrolled fracking represents a “politicized agenda . to stymie U.S. energy production.” This is ideological nonsense.

There is no dispute that natural gas is cleaner than coal or oil when burned, or that the nation would be better off if we reduced our dependence on foreign oil. But there is also no dispute that there are serious risks associated with hydrofracking, especially to the nation’s water resources.

Two such threats are cotaminating groundwater with the proprietary, often secret, mixes of industrial chemicals injected to fracture the formations, and the vast quantities of “produced water” that come up with natural gas and can contain fracking chemicals, radioactive elements and other contaminants.

Produced water from gas operations is often more toxic than water produced from petroleum production, and can contain high concentrations of salts, acids, benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene, xylene, radioactive materials and other nasty chemicals. Sometimes this produced water is sent to public wastewater plants ill-equipped to treat it; sometimes it is dumped into local waterways; sometimes regulators have no idea how much wastewater is produced or where the contaminated water goes because producers don’t tell them. As unconventional gas production has grown, drinking water wells have been contaminated; toxic wastewater, fracking fluids and diesel fuel have spilled into local watersheds; residents have been exposed to poisonous chemicals; and people have ignited gases coming out of their faucets with their water.

Additionally, methane leaks, from wellheads may worsen greenhouse gas emissions.

This isn’t right and it isn’t necessary. These environmental costs should be paid by industry, not dumped on the public.

Why do we have to expand domestic energy production the wrong way? Why the rush to bypass or prevent proper regulatory oversight? Expanding domestic energy production is important and reducing our use of more carbon -intensive oil and coal is critical, but natural gas is not our only option – the nation has vast renewable energy sources including solar, wind, biomass and geothermal to add to the mix. And protecting our groundwater, drinking water, and rivers is equally critical.

Current regulations are a complicated mix of federal rules, state rules and no rules at all. Efforts by Congress to provide shortcuts, subsidies and loopholes for gas producers make things worse. For example, Congress exempted produced water from regulation under the hazardous waste requirements of the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act. Regulations under other federal and state pollution laws are inconsistently applied and weakly enforced.

Failures to protect water quality will lead to more and unnecessary impacts on community health and the environment. Existing regulations need better enforcement, and new regulations must be put in place. Monitoring water contamination from fracking and proper disposal of produced water needs to be greatly expanded. Some states, including California, are moving forward with improved legislation, but national action is needed.

We want safe and clean energy options, but we also want safe and clean water. There is no need to sacrifice one for the other.

Peter Gleick and Heather Cooley are co-directors of the Water Program of the Pacific Institute in Oakland.

‘Frack’ oil wells draw California into debate

Steve Craig is used to oil companies operating near his ranch in the smooth, rounded hills of southern Monterey County. But Craig draws the line at “fracking.”

A company called Venoco Inc. wants to try hydraulic fracturing in the Hames Valley near Bradley, using a high-pressure blend of water, sand and chemicals to crack rocks deep underground and release oil locked in the stone.

The same technique has revolutionized America’s natural gas business in the past five years, boosting production and driving down prices. It has also been blamed for tainting groundwater near fracked wells, a charge that drilling companies deny.

Anyone living near the Hames Valley has long experience with the oil industry. The San Ardo oil field – a thicket of pipes, power lines and pump jacks – sits about 5 miles up Highway 101, a source of petroleum and jobs since 1947.

But the possibility of polluted water alarms Craig and others, who have appealed to the county government to block Venoco. The fact that California, so far, does not regulate fracking bothers Craig just as much.

“The agencies have not asked, ‘Who’s drilling? Which compounds are being used?’ “ said Craig, who directs a land-preservation group in Monterey County. “ ‘Where does it go? Does it move up through a fault in the next big earthquake?’ No one’s asking these questions.”

The fight over fracking has finally come to California.

Debates over banning or restricting the practice have raged in New York, Pennsylvania and other states. The U.S. government is studying its safety, while the oil and gas industry maintains that fracking poses no threat to the environment or public health.

Until recently, California remained out of the fray because environmentalists and politicians believed fracking wasn’t happening here.

But it is.

Venoco fracked two wells in Santa Barbara County earlier this year, much to the surprise of local officials. The company received permits from Monterey County to drill up to nine wells in the Hames Valley, but Craig and other activists appealed the permits. Farther north, the company plans to frack 20 wells in the Sacramento Basin this year, according to one of its financial reports.

fracking not tracked in state

Occidental Petroleum Corp., located in Los Angeles, fracked wells in Kern and Ventura counties this spring. The U.S. Bureau of Land Management plans to sell oil-development leases next month in Monterey County, atop a geologic formation that may require fracking to produce much oil or gas.

The small number of individual projects that have come to light in California suggests that the practice is nowhere near as widespread here as it is in states such as Pennsylvania and Texas, where fracking has been used on hundreds of new wells. But no one knows for certain because no one has kept track.

The California agency that regulates the oil and gas industry does not record the number and location of fracked wells, a fact that has astonished and angered some politicians and environmentalists. Nor does the agency – the Division of Oil, Gas & Geothermal Resources – require companies to disclose the chemicals they use in the process.

That may change. In June, the Assembly passed legislation sponsored by Assemblyman Bob Wieckowski, D-Fremont, that would force companies to report the location of each new fracked well as well as the chemicals used. The state, he said, must do a better job monitoring a practice that may become common here.

“This is a baby step,” Wieckowski said. “Most of the time we’re reactive in government. We wait until the hurricane hits, and then we say, ‘Maybe we shouldn’t have built homes there.’

Hydraulic fracturing involves pumping underground large quantities of pressurized water and sand, along with a mixture of chemicals. (The chemicals, which can include household substances such as citric acid and carcinogens such as benzene, typically make up 1 percent of all the material pumped into the well.) The intense pressure breaks the rock, creating a lattice of tiny cracks that the sand props open. Natural gas or oil trapped in the stone flow through the fissures toward the well.

In use since the 1940s, fracking is hardly new. But improvements in the technique, combined with other practices such as horizontal drilling, have unleashed a fracking boom.

Hydraulic fracturing has opened up access to natural gas deposits locked inside shale rock formations, deposits that in the past were considered impractical to tap. The biggest of those formations, the Marcellus Shale, stretches beneath New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania and West Virginia and holds an estimated 410 trillion cubic feet of gas, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration. That’s enough to meet all of America’s natural gas needs for 17 years.

As fracking’s use spread in the past five or six years, U.S. shale gas production jumped, rising from 1 trillion cubic feet in 2006 to 4.8 trillion cubic feet last year. Natural gas prices plunged 37 percent during the same period as a result. Home heating bills fell, too.

The boom, however, triggered a backlash.

Homeowners living near fracked wells complained that their drinking water had been contaminated with methane – the main component of natural gas – or other chemicals. Some discovered they could set fire to the methane bubbling from their tap water. A Duke University study earlier this year found elevated concentrations of methane in drinking-water wells that were close to fracking wells.

impact on water unknown

A poorly designed and executed well can allow methane to migrate toward the surface along the well’s exterior, said Erik Milito, director of exploration and production for the American Petroleum Institute, an oil-industry trade group. But that isn’t the case if the well is built right, protected from the surrounding rock by steel pipe and concrete.

And it is extremely unlikely, Milito said, for gas released by fracking to reach an aquifer by any other route.

“It’s the geology,” he said. “In between the aquifer and the well, it’s thousands of feet of impermeable rock.”

So far, no complaints about contaminated water have surfaced in California, according to Wieckowski and others studying the issue.

“We don’t have smoking guns here, with people lighting their faucets on fire,” said Bill Allayaud, California director of government relations for the Environmental Working Group. “It’s possible we have groundwater contamination. We don’t appear to. But we don’t have any regulatory system to tell us that.”

Most fracking in California appears to target oil deposits, rather than natural gas.

Drillers here have focused their attention on the Monterey Shale, which lies below the southern San Joaquin Valley and the coastal hills of Central California. Many of the state’s big, aging oil fields – some of which have been pumped for a century – spring from the Monterey Shale. But large amounts of petroleum may remain locked in rock formations too tight to tap with conventional drilling.

How much? A recent Energy Information Administration report estimated the Monterey Shale may hold 15.4 billion barrels of recoverable oil, more than any other shale formation in the United States. The country uses about 19 million barrels per day.

The Monterey Shale’s potential, however, remains unproved. California’s largest oil company, Chevron Corp., has been exploring the formation but remains unconvinced that it’s worth the investment.

“At this point, we just don’t see the volumetric production that delivers enough barrels at a rate to make it economically competitive,” said George Kirkland, Chevron’s executive vice president, speaking on a recent conference call with Wall Street analysts. “But we’ve got more work to do.”

Venoco, however, is betting big on the Monterey Shale. The company, based in Denver, plans to spend roughly $100 million exploring the formation this year, according to one of the company’s financial reports. By the end of the first quarter, the company had drilled 18 wells in the formation.

Venoco did not return calls seeking comment for this story.

Not all drilling in the Monterey Shale involves fracking, however. In a recent conference call with financial analysts, Venoco Chief Executive Officer Timothy Marquez said that conventional drilling techniques appear to work better, at least in the wells Venoco has drilled so far.

“When we look at the results to date, our analysis is that the majority of the (Monterey) play will be developed using less expensive vertical wells using acid instead of the much more expensive fracking,” Marquez said.

The company fracked two wells on the edge of Santa Barbara County’s wine country, between the towns of Los Alamos and Orcutt. County officials had issued Venoco permits to drill the wells but didn’t realize until afterward that fracking would be involved, said Doug Anthony, the county’s deputy director of planning and development.

regulation bill in the works

The discovery prompted tense community meetings, as residents worried that fracking could contaminate their water. The county warned Venoco that if the company wanted to frack any more wells, it would have to file an oil production plan and seek an additional permit for each well. Otherwise, Venoco could face fines.

“We’re really trying to get to get up to speed with this,” Anthony said. “We’ve been talking to the industry and saying, ‘Come on, let’s figure this out.’ They tell you it’s been going on here already. Well, OK, where? And to what extent? And how much water did you use?”

County governments have limited authority over oil and gas operations in California. The state’s Division of Oil, Gas & Geothermal Resources serves as the industry’s main regulator here. However, the division, which is part of the state Department of Conservation, does not have specific regulations for fracking, regarding it as just one of several techniques for wresting more oil and natural gas from the earth.

The oil industry views Wieckowski’s bill with caution. Different companies use different chemicals in different proportions to frack wells. Each regards its exact recipe as a trade secret, a potential edge against the competition.

So Wieckowski is seeking a compromise. His bill would require companies to make public the chemicals used in each well, but not the exact proportions. That approach may work. Some companies, including Occidental, already post that information on a publicly accessible website, called FracFocus.

“We’re optimistic that the bill will end up being something we can support,” said Tupper Hull, spokeswoman for the Western States Petroleum Association, a trade group. “He seems to appreciate that there’s a need to have some protection for competitively sensitive information.” E-mail David R. Baker at dbaker@sfchronicle.com.

A Big Shale Play in California Could Boost the Golden State’s Oil Patch By Robert Mayer on July 26, 2011

California stands poised for a crude rejuvenation of sorts, as development of the Monterey

Shale play holds a key to reversing the state’s decades-old trend of declining production.

Call it a “California revolution,” as does Phil McPherson, a senior research analyst with Global Hunter Securities.

Bakken and Eagle Ford, the all-stars of the U.S. shale crude plays, draw the headlines — and the investment dollars — but it is the Monterey that could hold the greatest potential.

In the Energy Information Administration’s recently released “Review of Emerging Resources,” the federal agency pegs the Monterey play at 15.42 billion barrels of technically recoverable oil, compared to the Bakken’s 3.59 billion and the Eagle Ford’s 3.35 billion.

The Monterey shale overlaps much of California’s traditional crude producing regions. It generally runs in two swaths: a roughly 50-mile wide ribbon running length of the San Joaquin Valley and coastal hills, and a Pacific Coast strip of similar width between Santa Barbara and Orange County.

Add to the mix an improved regulatory climate with faster permitting, an uptick in rig counts, and increased interest from independents, and California’s oil fields have become “a great place for investors to look,” McPherson said. “Their day in the sun is about to come.”

Challenges persist, however, such as community resistance to new drilling.

Unlike in Texas and North Dakota, home to the aforementioned shale plays, Californians — particularly those in the coastal cities — tend to resist embracing their state’s oil and gas heritage.

Excelaron, for instance, has seen its Huasna Valley oil field project in San Luis Obispo County endure repeated delays from organized community resistance. The Bureau of Land Management is facing a legal protest from environmental groups that seek to halt the federal agency’s lease sale in September of 2,600 acres for oil and gas shale exploration in the San Joaquin Valley.

Frankly, most Californians might be surprised to learn that their land of sun, beaches and wine is also the nation’s third largest crude producing state, churning out 558,000 b/d. Indeed, five of the country’s 20 largest fields are in California.

But the state’s oil fortunes have been on a downward trajectory. Oil production peaked in 1985 at 1.08 million b/d, and has since steadily dwindled. California’s proven reserves, too, peaked in the early 1980s at more than 5.0 billion barrels and have since dropped to 2.7 billion barrels by 2008.

Many of its large oil fields are pushing 100 years, such as the mammoth Beldridge South, and rely on Enhanced Oil Recovery techniques such as steam-flooding, to keep producing into the 21st century. And new offshore drilling still remains largely off-limits.

Hence the hope in the 1,752-square-mile Monterey Shale play, the largest of its kind in the nation. Venoco — with 158,000 acres of Monterey land — and Occidental Petroleum — with 873,000 acres — are wrapping up a joint-venture 500-square mile 3-D seismic survey of the southern San Joaquin Basin portion of the shale play.

Results in the play, so far, have been mixed: vertical drilling has been fairly successful to date, whereas horizontal drilling’s success remains more uncertain.

The Monterey remains a sleeper, but so too were the Eagle Ford and Bakken plays early in their development. Several years passed between the initial stages of production in the Bakken and the play’s first mention in large newspapers.

“It takes time for the mainstream to realize what’s going on,” McPherson said.

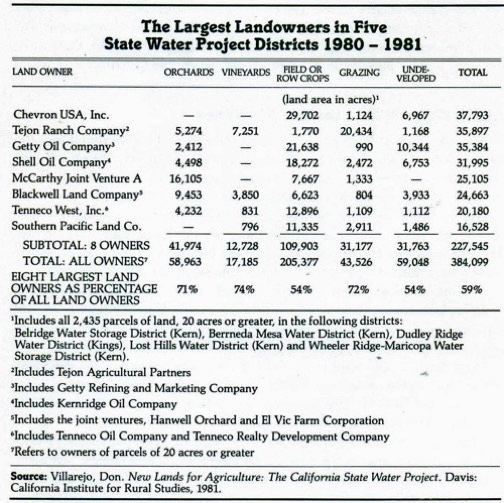

From pages 133-135 of Two Californias: the truth about the split-state movement byMichael DiLeo and Eleanor Smith:

Cheap Water + New Land = Big Money

“Some of these corporations bought up land in the Central Valley because of the vast oil deposits lying beneath many of the now-rich croplands. Since this oil is a thick and viscous crude that must be mined with steam, extractors need large volumes of water to develop it. Though they haven’t done so on a significant level yet, the petroleum giants of the Central Valley may soon be able to double their money by drilling and processing the black gold below their fields while they grow the highly profitable cash crops on the surface both with the aid of cheap state project water.”

Although it was designed to replenish the depleted underground aquifers in the Central Valley, the State Water Project actually served to bring new lands into production, A number of large corporations, foreseeing the enormous profits to be made once state water began flowing into previously unwatered areas of the valley, bought up huge tracts of land and installed irrigation systems. “The Tejon Ranch Company had its [irrigation) equipment in place when the first water came through because they had the capital to do so,” says Donald Villarejo of the California Institute for Rural Sludies.

The institute conducted a study entitled “New Lands for Agriculture,” which found that on the west side of the San Joaquin Valley, primarily in Kern County, which has no underground supplies, “about 250,000 acres have been placed in production as a direct result of State Water Project deliveries,”

More than 227,000 acres in this part of the valley, known as the Westlands Water District, are owned by Chevron USA Inc., Tejon Ranch Company, Getty Oil Company, Shell Oil Company, McCarthy Joint Venture A, Blackwell Land Company, Tenneco West Inc., and Southern Pacific Land Company,

‘The big corporations grow permanent, high-cash crops: almonds, pistachios, olives, and grapes, not exactly dinner table fare,” stated Thomas Schroeter, a Bakersfield attorney and former member of the defunct Kern County Planning Commission.

These corporations were attracted to the Central Valley not out of a love of farming but because of the tax benefits afforded to them if they grew the permanent crops. During the 1960s, the Internal Revenue Service allowed investors to immediately write off their entire share of development costs for growing almonds and other permanent crops.

Some of these corporations bought up land in the Central Valley because of the vast oil deposits lying beneath many of the now-rich croplands. Since this oil is a thick and viscous crude that must be mined with steam, extractors need large volumes of water to develop it. Though they haven’t done so on a significant level yet, the petroleum giants of the Central Valley may soon be able to double their money by drilling and processing the black gold below their fields while they grow the highly profitable cash crops on the surface both with the aid of cheap state project water.

Schroeter points out that the oil companies and other big corporations in Kern County “have no long-term commitment to agriculture. Blackwell Land Company [which has 13,000 acres of permanent crops and uses 42,000 acrefeet of SWP water a year] is not an agricultural company. Nor is Tejon Ranch Company, nor Tenneco, nor Shell, nor Prudential Insurance (which owns 75 percent of McCarthy Joint Venture A), nor are most of the others. They’re land developers.” 21

The Tejon Company has filed draft plans with the county to build a new community of 700,000 people, and other corporations have long-range plans for residential developments on their land, according to Schroeter and Villarejo.

What’s most interesting about all this corporate interest in Kern County agriculture is how it translates into the Barnum and Bailey arena of California water politics.

Ever since the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California helped tip the scales in favor of the State Water Project, it has teamed up with Central Valley growers to press for more water development. The happy alliance is based largely on a surplus of SWP water, which the MWD is entitled to but does not use. The surplus, which MWD must pay for in order to maintain its right to the water, in case the district ever does need it, goes to Kern County’s farmers at wildly reduced rates-about $3 to $4 an acre-foot. Although the state is obligated by law to sell any surplus SWP water to the highest bidder, it has never done so. Explains National Land for People board member David Nesmith, ‘They’ve taken it and sold it at the cheapest cost they could [just] to pay for transportation.”

Because MWD gets one-third of its income from property taxes in its vast service area, it is the urban water user who ends up subsidizing Kern’s farmers, many of them wealthy corporations. (See chapter 6 for more discussion of water subsidies.)

Arkansas ‘Fracking’ Site Closures Extended As Earthquake Link Studied By SARAH EDDINGTON

03/17/11 08:36 PM ET LITTLE ROCK, Ark. — Two natural gas exploration companies agreed Thursday to extend the shutdowns of two injection wells in Arkansas as researchers continue to study whether the operations are linked to a recent increase in earthquake activity, a state commission said.

Chesapeake Energy and Clarita Operating asked to postpone a hearing on the shutdowns before the Arkansas Oil and Gas Commission until April 26, said Shane Khoury, deputy director and general counsel for the commission.

The companies had been expected to present testimony to the commission on March 29, after the panel ordered the temporary shutdowns of the wells on March 4. The two injection wells are used to dispose of waste fluid from natural gas production.

“We were going to request that the wells remained shut down (at the meeting on March 29),” Khoury said. “(Both companies) requested a continuance on the hearing until April, and we agreed on the condition that the wells remain closed until that time.”

Khoury has said preliminary studies showed evidence potentially linking injection activities with more than 1,000 mostly minor quakes in the region during the past six months.

Clarita Operating has said it does not agree with the commission and it believes the area’s seismic activity is a result of natural causes. Clarita has not changed its position, Mickey Thompson, one of the company’s partners, said Thursday.

“We still very much believe that the science needs to be heard before any conclusions are drawn,” he said.

Thompson said the company is hoping its alliance with Chesapeake Energy, a larger company, will help strengthen its case. Chesapeake also says the earthquakes are likely a natural occurrence.

“The science continues to point to naturally occurring seismicity, but to ensure that we provide the most complete expert analysis, we have agreed with the commission staff to keep our disposal well temporarily closed until the … April hearing,” Danny Games, Chesapeake’s senior director of corporate development, said in a statement. “We will continue to work with all parties involved for a resolution, and we are appreciative of the cooperation and constructive exchange.”

The area has experienced a noticeable decrease in seismic activity since the injection wells have been closed, said Scott Ausbrooks, geohazards supervisor for the Arkansas Geological Survey. However, he said it is too early to tell if the two events are directly related.

The Center for Earthquake Research and Information recorded around 100 earthquakes in the seven days preceding the shutdown earlier this month, including the largest quake to hit the state in 35 years – a magnitude 4.7 on Feb. 27. A dozen of the quakes had magnitudes greater than 3.0.

In the seven days following the shutdown, there were around 50 earthquakes. Since the wells were shut down, only two quakes have been magnitude 3.0 or greater. The majority were between magnitudes 1.2 and 2.8.

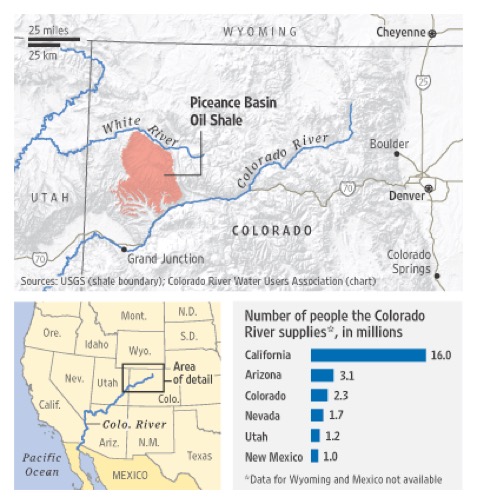

DENVER AND THE WEST: Oil-shale plans create ripple Companies accrue more than 250 water rights on Western Slope for energy development By Mark Jaffe, The Denver Post

Oil companies have amassed more than 250 water rights for oil-shale development, giving them a key share of the flow of the Colorado River and the White River, according to a Western Resource Advocates study.

Many of the water rights are also more senior than those held by Front Range water suppliers, and that could hamper plans to bring more water over the mountains for towns and cities, the study said.

“Large-scale oil-shale development could create problems for us and other users,” said Denver Water manager Chips Barry.

Six oil companies have filed for 7.2 million acre-feet of water rights on the Colorado and White rivers — equal to the entire allocation for the Upper Colorado River Basin.

The companies also control 104 agricultural irrigation ditch companies in the region, the Boulder-based environmental law center found.

Oil companies “have cornered the market” on the Western Slope water rights, said Karin Sheldon, Western Resource Advocates executive director.

Harris Sherman, the director of the state Department of Natural Resources, said “oil shale could be a game changer,” and the state’s role is to balance the need for water for energy development with the state’s other needs.

“There are a lot of assumptions being made,” said Tracy Boyd, a spokesman for Shell Exploration & Production — one of the companies trying to develop oil-shale extraction.

“We have acquired a number of water rights to maintain flexibility so we don’t impinge on other users,” Boyd said.

It will be decades before oil-shale development is viable, and the amount of water it will need is being overestimated, said Exxon Mobil spokesman Patrick McGinn.

Most of the oil-company rights are “conditional” and still need final water court approval. It is impossible to tell which will be awarded, which will be used and what other water users might be affected, Sheldon said.

Chris Treese, a spokesman for the Colorado River Water Conservation District, said, “Any large transfer of water to oil shale would shift the West Slope from an agricultural landscape to an industrial one.”

For the Front Range, the problem is that the water rights held by the oil companies date to the 1950s and have priority over the rights developed by water utilities in recent years.

For example, the Northern Colorado Water Conservancy District is spending $270 million on its Windy Gap project to bring water to Broomfield and other northern cities based on a 1967 water right.

“Yes, it is a concern to us,” said district spokesman Brian Werner. “The best you can do is monitor the situation and build your projects to give you flexibility.”

Denver Water’s concerns

Denver Water’s Barry said he was not concerned about the priorities. “Perfecting a conditional right isn’t a slam dunk anymore,” he said.

Denver Water’s concern is that any large diversion from the Colorado River might keep Colorado from being able to deliver the water it owes to states downstream.

Failure to deliver that water could lead to all Colorado water rights issued after the 1922 Colorado River Compact being cut to assure downstream flow to Arizona, California, Nevada, and parts of New Mexico and Utah.

“That is a risk not only for Denver Water but for the entire state,” Barry said.

The exercise of oil-shale water rights might also affect the snowmaking in Aspen, said Dave Bellach, Aspen Ski Co. senior vice president.

Aspen uses some ditch-company water for snowmaking in the winter, and if that was no longer available, it would have to be replaced, Bellach said.

Vail Resorts and several other ski resorts have over the past decade invested in senior water rights to assure their supplies, said Glenn Porzak, a water attorney for the company.

“The resorts saw the risk and tried to reduce it,” Porzak said.

Mark Jaffe: 303-954-1912 or mjaffe@denverpost.com

Oil, Water Are Volatile Mix in West: Energy Firms Buying River Rights Add to Competition for Scarce Resource By Stephanie Simon

DENVER — Oil companies have gained control over billions of gallons of water from Western rivers in preparation for future efforts to extract oil from shale deposits under the Rocky Mountains, according to a new report by an environmental group that opposes such projects. The group, Western Resource Advocates, used public records to conclude that energy companies are collectively entitled to divert more than 6.5 billion gallons of water a day during peak river flows. The companies also hold rights to store, in dozens of reservoirs, 1.7 million acre feet of water, enough to supply metro Denver for six years.

The group, Western Resource Advocates, used public records to conclude that energy companies are collectively entitled to divert more than 6.5 billion gallons of water a day during peak river flows. The companies also hold rights to store, in dozens of reservoirs, 1.7 million acre feet of water, enough to supply metro Denver for six years.

Industry representatives said they have substantial holdings of water rights for future use in producing oil from shale, though they could not confirm the precise numbers in the report.

Before any move into full-scale oil shale production, the energy industry plans a close study of water issues, including the impact its operations would have on ranchers, farmers and communities that all rely on the same limited sources of water, said Richard Ranger, a senior policy adviser for the American Petroleum Institute. “It’s among the most important questions to be examined,” he said.

Bitter fights over water are a recurring feature of life in the arid West, from Colorado to California, and energy companies are just the latest in a long list of users vying for the resource.

Extracting oil from shale is still an experimental process, facing major technological, environmental and regulatory hurdles, and is considerably more expensive than conventional drilling.

But if the price of oil rebounds, the potential payoff is big: the federal government estimates 800 billion barrels of oil, triple the known reserves of Saudi Arabia, lie under the Rocky Mountain West.

For now, the energy companies are not using most of the water they’ve claimed; they’re leasing some of it to other users, most often farmers. But they are stocking up on water rights to be sure they won’t be caught short.

Colorado River water supports 30 million people and dozens of uses,including power generation, above, at the Glen Canyon Dam in Arizona. Associated Press

“We’re picking up properties as they become available or look strategic,” said Tracy Boyd, a spokesman for Royal Dutch Shell PLC. Shell does not expect to need large quantities of water for at least 15 years, he said, and by then it may have developed less water-intensive ways to extract oil, perhaps using wind power.

Exxon Mobil Corp., too, said new technologies might reduce future water needs. “We continue to be a careful steward of this precious resource and a considerate neighbor in dry years,” said Patrick McGinn, a spokesman.

The Colorado River basin provides water to nearly 30 million people from the U.S. and Mexico, and irrigates 15% of the U.S.’s crops. Across the West, legions of lawyers and lobbyists fight to extract — or preserve — every precious drop.

Under Colorado law, river water is available, free of charge, to any entity that can show the water will be put to a “beneficial” use. Extracting oil fits into that category, as does, for example, growing alfalfa, providing household drinking water and making snow at ski resorts.

Oil companies can get water rights in two ways under the seniority system Colorado uses for appropriating water. For a minimal filing fee, the companies have claimed scores of “junior” rights that allow them to draw water from a particular river after other users have satisfied their needs. The companies have also purchased dozens of “senior” rights from old-time farming families; those rights give them priority access to water, even in dry years.

Even if the oil companies use every last drop of their entitlements — a scenario widely considered improbable — there’s no risk of the Colorado River drying up.

But a 1922 compact requires the river’s flow to be divided among seven U.S. states and Mexico. If oil shale takes off, it could well use up the last of Colorado’s allotment, said Eric Kuhn, who runs the Colorado River Water Conservation District.

That would leave the booming suburban communities around Denver high and dry, with no water to support future growth, Mr. Kuhn said.

The Shell spokesman, Mr. Boyd, disputed that: “I don’t believe that’s anywhere near true.”

Write to Stephanie Simon at stephanie.simon@wsj.com

Corrections & Amplifications

A previous version of this article incompletely characterized the Colorado River basin. The basin provides water to nearly 30 million people in the U.S. and Mexico, not just the U.S..