Big Energy Frackers Keep on Fracking With Their Own Private Water Supplies During Drought

December 2022 Update:

Newsom is Pro-Oil, As California is Thristy!: Drought-Wracked California Allows Oil Companies to Use High-Quality Water. But Regulators’ Error-Strewn Records Make Accurate Accounting Nearly Impossible. California’s oil industry uses hundreds of millions of gallons of freshwater a year in a state with none to spare. Most of that water is used in Kern County, where communities have long lacked affordable, safe drinking water. Last month, with California in the grips of a megadrought, Gov. Gavin Newsom announced a plan centered on “the acute need to conserve water” in the face of a drier, hotter future caused by climate change. The plan outlines actions to “transform water management” and calls on California residents to step up and do their part to conserve water. Yet the plan does nothing to limit use of California’s dwindling water supplies by one of the primary drivers of climate change: the oil and gas industry. An Inside Climate News analysis of data collected by the California Geologic Energy Management Division, or CalGEM, shows high-quality water is being diverted from state domestic and agricultural supplies, predominantly in Kern County, to extract viscous crude from some of the world’s most climate-polluting oilfields.

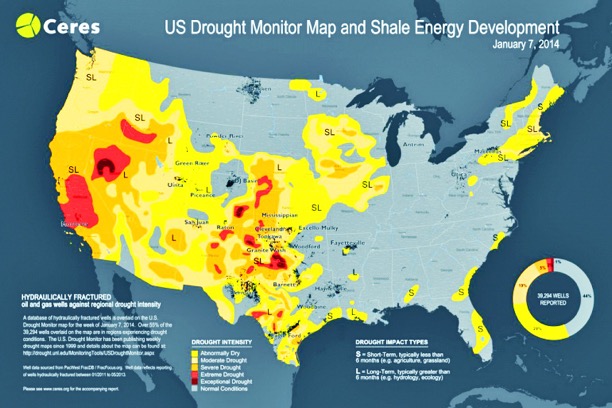

More than 55 percent of all U.S. wells are operated in areas experiencing a level of drought. Ceres

As there is now a shortage of drinking water in the Western United States There Is no shortage of water for fracking.

While the West is in drought, Big energy and Agribusiness are not. As big contributors to election campaigns they have acquired enough water reserves to keep fracking during the drought as fresh water dries up for the citizens of California. On February 7, I watched the Linda Yee WKPIX News Special:

Group Sues California For Privatizing Massive Water Reserve

California is in a drought so serious, Gov. Jerry Brown has declared a state of emergency. Yet a handful of the state’s biggest agribusinesses may not be feeling the pinch as much.

The Golden State is bone dry. “Make no mistake, this is a mega-drought,” Brown said just last week. The worst drought on record has delivered virtually no snowpack, drained reservoirs and turned once lush vineyards brown. Mandatory rationing is in the works.

But there is one place where there’s no shortage of water. The bountiful pomegranate, almond and pistachio fields of paramount farms are as green as ever.

You wouldn’t know it because you can’t see it. But there is a huge underground water reservoir on the south end of the Central valley, near Bakersfield. It’s four times as big as Hetch Hetchy reservoir, (which supplies the city of San Francisco with its water).

It’s called the Kern Water Bank. And it’s majority controlled by two of the state’s biggest agribusinesses: Paramount Farms, a division of Roll International, and Tejon Ranch Company.

“I agree that it’s a big water bank, said Katy Spanos, an attorney with the California Department of Water Resources. Spanos said the state turned the huge underground aquifer over to a handful of big agribusinesses almost 20 years ago, in exchange for a cutback on their state water allotments.

But no money was exchanged. In fact, the state lost money, because it had originally paid about $70 million for the land the Kern Water Bank sits on.

Spanos told KPIX 5 the cost of building a bank is significantly more than that. “Water managers feel that this is the kind of thing that makes good sense,” she said.

But not everyone agrees. “I don’t think in this country we are prepared to allow fresh water to be a privately controlled resource,” said Adam Keats, a senior attorney with the Center for Biological Diversity.

His group, along with California Sportfishing Alliance, several Delta water districts and ratepayers, are suing the state to get the water bank back. The suit claims the transfer of the Kern Water Bank to controlling private interests “amounts to an unlawful and unconstitutional gift of a critical state asset.”

“This is as important as some of the largest dammed reservoirs in the state,” said Keats. “What our lawsuit is about is to try to say hey, you can’t just rewrite the contracts on these things.”

Keats predicts the private ownership of that much water will lead to speculation, and profitmaking.

“The drought is a perfect opportunity for them to do so. I think they are trying to lay low until they feel they have a more solid grasp on this water. And then the proverbial floodgates are going to open and we are going to see the damage that these guys have engineered,” he said.

Katy Spanos disagrees. “We don’t see any signs that it will be used to sell water outside the service area,” she said.

But she admits the state no longer has control over the water in the Kern Water Bank. “We don’t look at the end use,” she said.

Keats said, “Should we leave it to a couple of rich guys to decide how to distribute it, or should we let that be the democratic process that our governor and our elected officials if they really had our interests at heart, would distribute fairly?”

A judge heard arguments last week on claims the transfer of the Kern Water Bank violates California’s environmental laws. A decision is expected in a couple of weeks.

KERN COUNTY (KPIX 5) — California is in a drought so serious, Gov. Jerry Brown has declared a state of emergency. Yet a handful of the state’s biggest agribusinesses may not be feeling the pinch as much.

The Golden State is bone dry. “Make no mistake, this is a mega-drought,” Brown said just last week. The worst drought on record has delivered virtually no snowpack, drained reservoirs and turned once lush vineyards brown. Mandatory rationing is in the works.

But there is one place where there’s no shortage of water. The bountiful pomegranate, almond and pistachio fields of paramount farms are as green as ever.

You wouldn’t know it because you can’t see it. But there is a huge underground water reservoir on the south end of the Central Valley, near Bakersfield. It’s four times as big as Hetch Hetchy reservoir.

It’s called the Kern Water Bank. And it’s majority controlled by two of the state’s biggest agribusinesses: Paramount Farms, a division of Roll International, and Tejon Ranch Company.

“I agree that it’s a big water bank, said Katy Spanos, an attorney with the California Department of Water Resources. Spanos said the state turned the huge underground aquifer over to a handful of big agribusinesses almost 20 years ago, in exchange for a cutback on their state water allotments.

But no money was exchanged. In fact, the state lost money, because it had originally paid about $70 million for the land the Kern Water Bank sits on.

Spanos told KPIX 5 the cost of building a bank is significantly more than that. “Water managers feel that this is the kind of thing that makes good sense,” she said.

But not everyone agrees. “I don’t think in this country we are prepared to allow fresh water to be a privately controlled resource,” said Adam Keats, a senior attorney with the Center for Biological Diversity.

His group, along with California Sportfishing Alliance, several Delta water districts and ratepayers, are suing the state to get the water bank back. The suit claims the transfer of the Kern Water Bank to controlling private interests “amounts to an unlawful and unconstitutional gift of a critical state asset.”

“This is as important as some of the largest dammed reservoirs in the state,” said Keats. “What our lawsuit is about is to try to say hey, you can’t just rewrite the contracts on these things.”

Keats predicts the private ownership of that much water will lead to speculation, and profitmaking.

“The drought is a perfect opportunity for them to do so. I think they are trying to lay low until they feel they have a more solid grasp on this water. And then the proverbial floodgates are going to open and we are going to see the damage that these guys have engineered,” he said.

Katy Spanos disagrees. “We don’t see any signs that it will be used to sell water outside the service area,” she said.

But she admits the state no longer has control over the water in the Kern Water Bank. “We don’t look at the end use,” she said.

Keats said, “Should we leave it to a couple of rich guys to decide how to distribute it, or should we let that be the democratic process that our governor and our elected officials if they really had our interests at heart, would distribute fairly?”

A judge heard arguments last week on claims the transfer of the Kern Water Bank violates California’s environmental laws. A decision is expected in a couple of weeks.

* * *

What the story did not point out that the Tejon Ranch has also been fracking/pumping out oil for years in California. And they are pumping using move and more water.:

At the peak of California production in 1985, Kern County producers needed roughly four-and-a-half barrels of water to produce a single barrel of oil. Today, that ratio has jumped to almost eight barrels of water per barrel of oil. This use has been sanctioned despite the three-year drought that has ravaged the valley, causing reductions in the water delivered by the State and Central Valley projects canals. Not only are farmers generally short of water, dozens of small poor agricultural hamlets — including Alpaugh, Seville, East Orosi and Kettleman City — have been forced to tap groundwater. And that groundwater is often contaminated with agricultural pollutants, including arsenic and nitrates. — Oil and Water Don’t Mix with California Agriculture

* * *

From pages 133-135 of the book, Two Californias: the truth about the split-state movement by Michael DiLeo and Eleanor Smith:

Cheap Water + New Land = Big Money

Some of these corporations bought up land in the Central Valley because of the vast oil deposits lying beneath many of the now-rich croplands. Since this oil is a thick and viscous crude that must be mined with steam, extractors need large volumes of water to develop it. Though they haven’t done so on a significant level yet, the petroleum giants of the Central Valley may soon be able to double their money by drilling and processing the black gold below their fields while they grow the highly profitable cash crops on the surface both with the aid of cheap state project water.

Although it was designed to replenish the depleted underground aquifers in the Central Valley, the State Water Project actually served to bring new lands into production, A number of large corporations, foreseeing the enormous profits to be made once state water began flowing into previously unwatered areas of the valley, bought up huge tracts of land and installed irrigation systems. “The Tejon Ranch Company had its [irrigation) equipment in place when the first water came through because they had the capital to do so,” says Donald Villarejo of the California Institute for Rural Sludies.

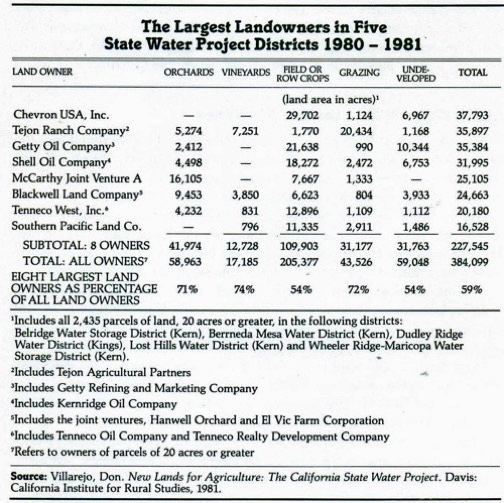

The institute conducted a study entitled “New Lands for Agriculture,” which found that on the west side of the San Joaquin Valley, primarily in Kern County, which has no underground supplies, “about 250,000 acres have been placed in production as a direct result of State Water Project deliveries,”

More than 227,000 acres in this part of the valley, known as the Westlands Water District, are owned by Chevron USA Inc., Tejon Ranch Company, Getty Oil Company, Shell Oil Company, McCarthy Joint Venture A, Blackwell Land Company, Tenneco West Inc., and Southern Pacific Land Company,

‘The big corporations grow permanent, high-cash crops: almonds, pistachios, olives, and grapes, not exactly dinner table fare,” stated Thomas Schroeter, a Bakersfield attorney and former member of the defunct Kern County Planning Commission.

These corporations were attracted to the Central Valley not out of a love of farming but because of the tax benefits afforded to them if they grew the permanent crops. During the 1960s, the Internal Revenue Service allowed investors to immediately write off their entire share of development costs for growing almonds and other permanent crops.

Some of these corporations bought up land in the Central Valley because of the vast oil deposits lying beneath many of the now-rich croplands. Since this oil is a thick and viscous crude that must be mined with steam, extractors need large volumes of water to develop it. Though they haven’t done so on a significant level yet, the petroleum giants of the Central Valley may soon be able to double their money by drilling and processing the black gold below their fields while they grow the highly profitable cash crops on the surface both with the aid of cheap state project water.

Schroeter points out that the oil companies and other big corporations in Kern County “have no long-term commitment to agriculture. Blackwell Land Company [which has 13,000 acres of permanent crops and uses 42,000 acrefeet of SWP water a year] is not an agricultural company. Nor is Tejon Ranch Company, nor Tenneco, nor Shell, nor Prudential Insurance (which owns 7S percent of McCarthy Joint Venture A), nor are most of the others. They’re “land developers.”‘

The Tejon Company has filed draft plans with the county to build a new community of 700,000 people, and other corporations have long-range plans for residential developments on their land, according to Schroeter and Villarejo.

What’s most interesting about all this corporate interest in Kern County agriculture is how it translates into the Barnum and Bailey arena of California water politics.

Ever since the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California helped tip the scales in favor of the State Water Project, it has teamed up with Central Valley growers to press for more water development. The happy alliance is based largely on a surplus of SWP water, which the MWD is entitled, to but does not use. The surplus, which MWD must pay for in order to maintain its right to the water, in case the district ever does need it, goes to Kern County’s farmers at wildly reduced rates-about $3 to $4 an acre-foot. Although the state is obligated by law to sell any surplus SWP water to the highest bidder, it has never done so. Explains National Land for People board member David Nesmith, ‘They’ve taken it and sold it at the cheapest cost they could [just] to pay for transportation.”

Because MWD gets one-third of its income from property taxes in its vast service area, it is the urban water user who ends up subsidizing Kern’s farmers, many of them wealthy corporations. (See chapter 6 for more discussion of water subsidies.)

Schroeter points out that the oil companies and other big corporations in Kern County “have no long-term commitment to agriculture. Blackwell Land Company (which has 13,000 acres of permanent crops and uses 42,000 acrefeet of SWP water a year) is not an agricultural company. Nor is Tejon Ranch Company, nor Tenneco, nor Shell, nor Prudential Insurance (which owns 75 percent of McCarthy Joint Venture A), nor are most of the others. They’re land developers.” 21

The Tejon Company has filed draft plans with the county to build a new community of 700,000 people, and other corporations have long-range plans for residential developments on their land, according to Schroeter and Villarejo.

What’s most interesting about all this corporate interest in Kern County agriculture is how it translates into the Barnum and Bailey arena of California water politics.

Ever since the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California helped tip the scales in favor of the State Water Project, it has teamed up with Central Valley growers to press for more water development. The happy alliance is based largely on a surplus of SWP water, which the MWD is entitled to but does not use. The surplus, which MWD must pay for in order to maintain its right to the water, in case the district ever does need it, goes to Kern County’s farmers at wildly reduced rates-about $3 to $4 an acre-foot. Although the state is obligated by law to sell any surplus SWP water to the highest bidder, it has never done so. Explains National Land for People board member David Nesmith, ‘They’ve taken it and sold it at the cheapest cost they could [just] to pay for transportation.”

Because MWD gets one-third of its income from property taxes in its vast service area, it is the urban water user who ends up subsidizing Kern’s farmers, many of them wealthy corporations. (See chapter 6 for more discussion of water subsidies.)

* * *

The practice of privatizing water by the energy conglomerates seem to be wide spread. This older article from the Wall Street Journal makes it quite clear:

Oil, Water Are Volatile Mix in West Energy Firms Buying River Rights Add to Competition for Scarce Resource By Stephanie Simon

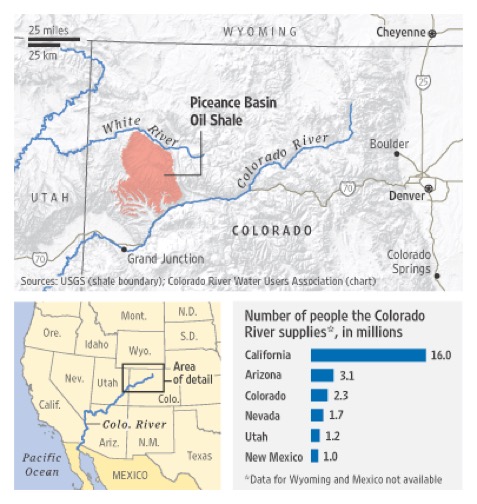

2009 Oil companies have gained control over billions of gallons of water from Western rivers in preparation for future efforts to extract oil from shale deposits under the Rocky Mountains, according to a new report by an environmental group that opposes such projects.

The group, Western Resource Advocates, used public records to conclude that energy companies are collectively entitled to divert more than 6.5 billion gallons of water a day during peak river flows. The companies also hold rights to store, in dozens of reservoirs, 1.7 million acre feet of water, enough to supply metro Denver for six years.

Industry representatives said they have substantial holdings of water rights for future use in producing oil from shale, though they could not confirm the precise numbers in the report.

Before any move into full-scale oil shale production, the energy industry plans a close study of water issues, including the impact its operations would have on ranchers, farmers and communities that all rely on the same limited sources of water, said Richard Ranger, a senior policy adviser for the American Petroleum Institute. “It’s among the most important questions to be examined,” he said.

Bitter fights over water are a recurring feature of life in the arid West, from Colorado to California, and energy companies are just the latest in a long list of users vying for the resource.

Extracting oil from shale is still an experimental process, facing major technological, environmental and regulatory hurdles, and is considerably more expensive than conventional drilling.

But if the price of oil rebounds, the potential payoff is big: the federal government estimates 800 billion barrels of oil, triple the known reserves of Saudi Arabia, lie under the Rocky Mountain West.

For now, the energy companies are not using most of the water they’ve claimed; they’re leasing some of it to other users, most often farmers. But they are stocking up on water rights to be sure they won’t be caught short.

Colorado River water supports 30 million people and dozens of uses, including power generation, above, at the Glen Canyon Dam in Arizona. Associated Press

Colorado River water supports 30 million people and dozens of uses, including power generation, above, at the Glen Canyon Dam in Arizona. Associated Press

“We’re picking up properties as they become available or look strategic,” said Tracy Boyd, a spokesman for Royal Dutch Shell PLC. Shell does not expect to need large quantities of water for at least 15 years, he said, and by then it may have developed less water-intensive ways to extract oil, perhaps using wind power.

Exxon Mobil Corp., too, said new technologies might reduce future water needs. “We continue to be a careful steward of this precious resource and a considerate neighbor in dry years,” said Patrick McGinn, a spokesman.

The Colorado River basin provides water to nearly 30 million people from the U.S. and Mexico, and irrigates 15% of the U.S.’s crops. Across the West, legions of lawyers and lobbyists fight to extract — or preserve — every precious drop.

Under Colorado law, river water is available, free of charge, to any entity that can show the water will be put to a “beneficial” use. Extracting oil fits into that category, as does, for example, growing alfalfa, providing household drinking water and making snow at ski resorts.

Oil companies can get water rights in two ways under the seniority system Colorado uses for appropriating water. For a minimal filing fee, the companies have claimed scores of “junior” rights that allow them to draw water from a particular river after other users have satisfied their needs. The companies have also purchased dozens of “senior” rights from old-time farming families; those rights give them priority access to water, even in dry years.

Even if the oil companies use every last drop of their entitlements — a scenario widely considered improbable — there’s no risk of the Colorado River drying up.

But a 1922 compact requires the river’s flow to be divided among seven U.S. states and Mexico. If oil shale takes off, it could well use up the last of Colorado’s allotment, said Eric Kuhn, who runs the Colorado River Water Conservation District.

That would leave the booming suburban communities around Denver high and dry, with no water to support future growth, Mr. Kuhn said.

The Shell spokesman, Mr. Boyd, disputed that: “I don’t believe that’s anywhere near true.”

Write to Stephanie Simon at [email protected]

* * *