The Rise and Fall of the Civil Rights Movement

The Rise and Fall of the Civil Rights Movement (Kindle Price: $5.99) 1963 Civil Rights March on Washington

1963 Civil Rights March on Washington Preface

Preface

‘The House Negro and the Field Negro’

“. . . Back during slavery. There was two kinds of slaves. There was the house Negro and the field Negro. The house Negroes – they lived in the house with master, they dressed pretty good, they ate good ’cause they ate his food — what he left. They lived in the attic or the basement, but still they lived near the master; and they loved their master more than the master loved himself. They would give their life to save the master’s house quicker than the master would. The house Negro, if the master said, “We got a good house here,” the house Negro would say, “Yeah, we got a good house here.” Whenever the master said “we,” he said “we.” That’s how you can tell a house Negro. If the master’s house caught on fire, the house Negro would fight harder to put the blaze out than the master would. If the master got sick, the house Negro would say, “What’s the matter, boss, we sick?” We sick! He identified himself with his master more than his master identified with himself. And if you came to the house Negro and said, “Let’s run away, let’s escape, let’s separate,” the house Negro would look at you and say, “Man, you crazy. What you mean, separate? Where is there a better house than this? Where can I wear better clothes than this? Where can I eat better food than this?” That was that house Negro. In those days he was called a “house nigger.” And that’s what we call him today, because we’ve still got some house niggers running around here. This modern house Negro loves his master. He wants to live near him. He’ll pay three times as much as the house is worth just to live near his master, and then brag about “I’m the only Negro out here.” “I’m the only one on my job.” “I’m the only one in this school.” You’re nothing but a house Negro. And if someone comes to you right now and says, “Let’s separate,” you say the same thing that the house Negro said on the plantation. ‘What you mean, separate? From America? This good white man? Where you going to get a better job than you get here?’ I mean, this is what you say. ‘I ain’t left nothing in Africa, that’s what you say. Why, you left your mind in Africa. On that same plantation, there was the field Negro. The field Negro — those were the masses. There were always more Negroes in the field than there was Negroes in the house. The Negro in the field caught hell. He ate leftovers. In the house they ate high up on the hog. The Negro in the field didn’t get nothing but what was left of the insides of the hog. They call ’em ‘chitt’lin’ nowadays. In those days they called them what they were: guts. That’s what you were — a gut-eater. And some of you all still gut-eaters. The field Negro was beaten from morning to night. He lived in a shack, in a hut; He wore old, castoff clothes. He hated his master. I say he hated his master. He was intelligent. That house Negro loved his master. But that field Negro — remember, they were in the majority, and they hated the master. When the house caught on fire, he didn’t try and put it out; that field Negro prayed for a wind, for a breeze. When the master got sick, the field Negro prayed that he’d die. If someone come [sic] to the field Negro and said, ‘Let’s separate, let’s run,’ he didn’t say ‘Where we going?’ He’d say, ‘Any place is better than here. You’ve got field Negroes in America today. I’m a field Negro. The masses are the field Negroes. When they see this man’s house on fire, you don’t hear these little Negroes talking about ‘our government is in trouble.’ They say, ‘The government is in trouble.’ Imagine a Negro: ‘Our government’! I even heard one say ‘our astronauts’ They won’t even let him near the plant — and “our astronauts”! ‘Our Navy’ — that’s a Negro that’s out of his mind. That’s a Negro that’s out of his mind. Just as the slavemaster of that day used Tom, the house Negro, to keep the field Negroes in check, the same old slavemaster today has Negroes who are nothing but modern Uncle Toms, 20th century Uncle Toms, to keep you and me in check, keep us under control, keep us passive and peaceful and nonviolent. That’s Tom making you nonviolent. It’s like when you go to the dentist, and the man’s going to take your tooth. You’re going to fight him when he starts pulling. So he squirts some stuff in your jaw called novocaine, to make you think they’re not doing anything to you. So you sit there and ’cause you’ve got all of that novocaine in your jaw, you suffer peacefully. Blood running all down your jaw, and you don’t know what’s happening. ’Cause someone has taught you to suffer — peacefully.” — Malcolm X, The House Negro and the Field Negro

“Negro leaders suffer from this interplay of solidarity and divisiveness, being either exalted excessively or grossly abused. Some of these leaders suffer from an aloofness and absence of faith in their people. The white establishment is skilled in flattering and cultivating emerging leaders. It presses its own image on them and finally, from imitation of manners, dress and style of living, a deeper strain of corruption develops. This kind of Negro leader acquires the white man’s contempt for the ordinary Negro. He is often more at home with the middle-class white than he is among his own people. His language changes, his location changes, his income changes, and ultimately he changes from the representative of the Negro to the white man into the white man’s representative of the Negro. The tragedy is that too often he does not recognize what has happened to him.” — Martin Luther King Jr. 1967, The Black Power Defined

The Rise and Fall of the Civil Rights Movement

(This article was originally publish on September 5, 2006, by Counterpunch.com under the title: Where Will Blacks Find Justice? The Civil Rights Movement is Dead and So is the Democratic Party.)

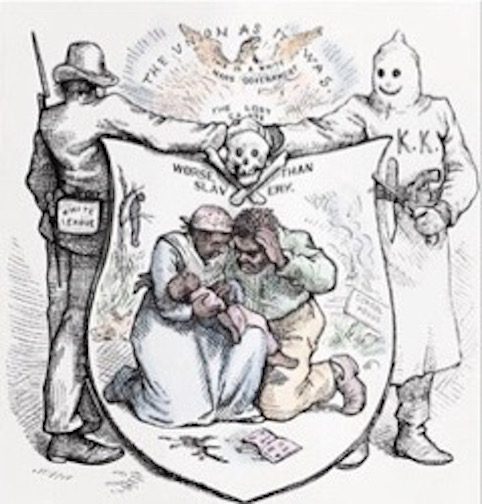

The first civil and human rights movement by and for Black people started during the Civil War and the period of Black Reconstruction that followed. It was a time of radical hopes for many freed slaves. But it was also a time of betrayal. Then President Andrew Johnson and the non-radical Republicans, in collusion with the Democratic Party, the party of slavery, sold out the early post-war promises for full equality and “40 acres and a mule”. Instead, the promise of equality was soon replaced by the restoration of the property rights of the former slave owners in the South. This was accomplished by the Compromise of 1877. Thomas Nast,at that times illestrated the results ofthat betrayal.

Harper’s Weekly Cartoons by Thomas Nast Depicting the Plight of African-Americans During Reconstruction and His View of the “Compromise” of 1877: “Compromise—Indeed! How did they accomplish this betrayal? The answer is simple— The answer is simple —By the Use of Terrorism! — They used police and terroristic Ku Klux Klan violence. These extra-legal and ‘legal’ activities laid the basis for the overthrow of Black Reconstruction and the institutionalization of legal segregation (Jim Crow) in the former slave states. To enforce Jim Crow, Black people were, for decades, indiscriminately lynched and framed.

How did they accomplish this betrayal? The answer is simple— The answer is simple —By the Use of Terrorism! — They used police and terroristic Ku Klux Klan violence. These extra-legal and ‘legal’ activities laid the basis for the overthrow of Black Reconstruction and the institutionalization of legal segregation (Jim Crow) in the former slave states. To enforce Jim Crow, Black people were, for decades, indiscriminately lynched and framed.

This was the status quo in the United States until the United States Supreme Court came out with its “Brown v. Board of Education” decision in 1954, mandating the right to equal education. The successful yearlong Montgomery Bus Boycott in 1955-56 reflected the new, more militant mood among Negroes (the name given to Black people by the ruling class). This new mood was a product of the rise of the Black Liberation movements in Africa, the confidence gained by the Black working class during the rise of the CIO, and the respect, knowledge, and expectations of democracy gained by Black soldiers during the Korean War.”1 (For more information about the boycott read my article: 50 Years Later: Lessons from the Montgomery Bus Boycott.)

Thus the struggle against Jim Crow had begun, and with each victory to integrate and enforce the 1954 Supreme Court decision, the mass of Black people gained confidence in themselves and that the fight for racial equality could be won. In the early sixties, the movement grew stronger as young people from the universities spearheaded the ‘freedom rides’ and sit-ins throughout the South to oppose Jim Crow and enforce the law of the land, which the local, state, and federal governments had refused to enforce.

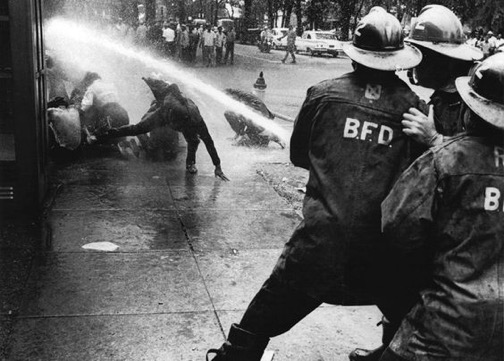

In the spring of 1963, the struggles in Birmingham, Alabama, led by the Black working class, garnered international attention when police commissioner Eugene (”Bull”) Connor unleashed powerful water hoses and German shepherd police dogs against the demonstrators. Terror and violence gripped this city, while the world watched. Indeed, it was the national and international embarrassment that forced President Kennedy and the government to begin to take governmental action.

Dogs Attacking Birmingham Black Citizens in 1963

Firefighters Pressure Hosing ‘terrorists’

After Birmingham, the March on Washington was called. In the space of a few months, a huge demonstration was built. This demonstration was the largest social action in the United States since the mass strikes that led to the rise of the CIO in the 1930s and late 1940s. This mass action led to the 1963 marcharch on Washington and Rally and the passage 5h3 ≈ of the Civil Rights Act in 1965.

At that rally, the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) Chairman John Lewis was prevented from delivering his prepared speech by the march organizers. It was a notable omission.

In this speech, he was going to say:

. . . . We are now involved in a serious revolution. This nation is still a place of cheap political leaders who build their career on immoral compromises and ally themselves with open forms of political, economic and social exploitation. What political leader here can stand up and say ‘My party is the party of “principles”’? The party of Kennedy is also the party of Eastland. The party of Javits is also the party of Goldwater. Where is our party? . . .

But if Lewis could be prevented by the March organizers from offending the liberal Democratic establishment from the stage of the Washington march, they could not prevent the civil rights movement from embracing a growing militancy and desire to expand the struggle to embrace a larger vision of social change.

Unfortunately, the momentum that was gained from the March was lost during the 1964 Presidential election campaign, when the major civil rights groups called for a moratorium on demonstrations in order not to embarrass then President Lyndon Baines Johnson during the election campaign against the “greater evil” Barry Goldwater. (Both were defenders of Jim Crow prior to the 1963 March on Washington.) The movement never fully recovered to this subordination of the struggle to “lesser evil” political action.

While the struggle in the South was specifically against Jim Crow, the struggle in the North was against de-facto segregation. The images of the dogs etc. on TV being used against Blacks in the South subsequently gave rise to the Black Nationalist movement in the North. The rise of the Black Muslims and Malcolm X was a reflection of the mood in the majority of the Black ghettos in every major northern city, where the economic and political power of Black people was more concentrated and greater than in the rural south. The rise of the nationalist movement consequently generated heated debates within the movement between the strategies of peaceful disobedience and righteous self-defense.

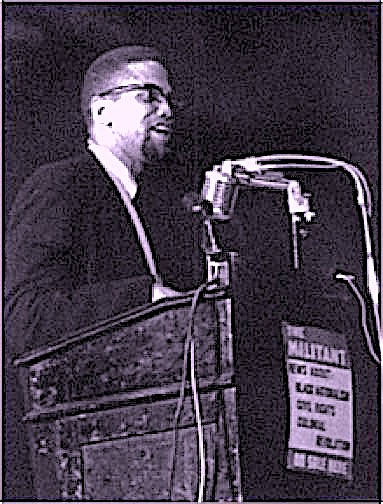

In his latter years, Malcolm X saw the Black struggle as a struggle for human rights, and, notably, as an anti-capitalist economic struggle. As he explained at the Militant Labor Forum in the fall of 1964:

It’s impossible for a chicken to produce a duck egg… The system in this country cannot produce freedom for an Afro-American. It is impossible for this system, this economic system, this political system, period… And if ever a chicken did produce a duck egg, I’m certain you would say it was certainly a revolutionary chicken.” — Malcolm X, Harlem ‘Hate Gang’ Scare Militant Labor Forum, May 29, 1964

Malcolm X speaking at the New York Militant Labor Forum, 1964 Photo by Eli (Lucky) Finer

Unfortunately, Malcolm X was assassinated in 1965 before he could build an organization to follow in his footsteps.

However, righteous self-defense, became a call of the Deacons for Defense and Justice, during this time:

The Deacons for Defense and Justice was an armed self-defense African-American civil rights organization in the U.S. Southern states during the 1960s. Historically, the organization practiced self-defense methods in the face of racist oppression that was carried out under the Jim Crow Laws by local/state government officials and racist vigilantes. Many times the Deacons are not written about or cited when speaking of the Civil Rights Movement because their agenda of self-defense – in this case, using violence, if necessary – did not fit the image of strict non-violence that leaders such as Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. espoused. Yet, there has been a recent debate over the crucial role the Deacons and other lesser known militant organizations played on local levels throughout much of the rural South. Many times in these areas the Federal government did not always have complete control over to enforce such laws like the Civil Rights Act of 1964 or Voting Rights Act of 1965. The Deacons were instrumental in many campaigns led by the Civil Rights Movement. A good example is the June 1966 March Against Fear, which went from Memphis, Tennessee, to Jackson, Mississippi. The March Against Fear signified a shift in character and power in the southern civil rights movement and was an event in which the Deacons participated. . .Scholar Akinyele O. Umoja speaks about the group’s effort more specifically. According to Umoja it was the urging of Stokely Carmichael that the Deacons were to be used as security for the march. Many times protection from the federal or state government was either inadequate or not given, even while knowing that groups like the Klan would commit violent acts against civil rights workers. An example of this was the Freedom Ride where many non-violent activists became the targets of assault for angry White mobs. After some debate and discussion many of the civil rights leaders compromised their strict non-violent beliefs and allowed the Deacons to be used. One such person was Dr. King. Umoja states, “Finally, though expressing reservations, King conceded to Carmichael’s proposals to maintain unity in the march and the movement. The involvement and association of the Deacons with the march signified a shift in the civil rights movement, which had been popularly projected as a ‘nonviolent movement.”‘[7]— Wilkipedia

Deacons for Defense

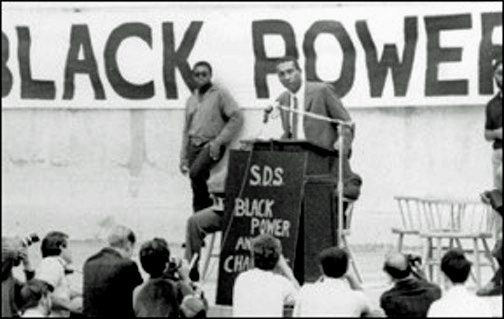

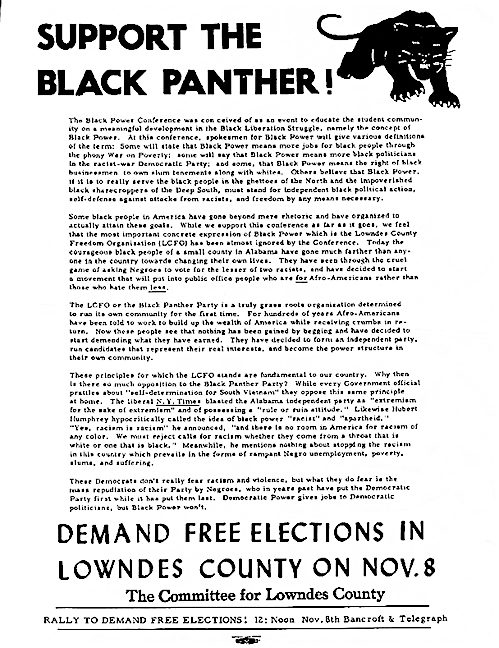

Following the assassination of Malcolm X, Stokely Carmichael, later known as Kwame Ture, became the new leader of SNCC and is credited with starting the movement for Black Power. In Lowndes County Alabama in 1965, he helped the Lowndes Country Freedom Organization (LCFO) to form their own party. The symbol of the party was the Black Panther and they were called the Black Panthers because of that symbol. The Alabama Democrats retaliated against this movement by evicting sharecroppers and tenant farmers, and attempting illegal foreclosures against Black Panther supporters. They even threatened to kill any African-American who registered. Thus the political activities of the LCFO inspired the formation of the Black Panther Party in Oakland, Calif. And, in the course of time, Black Panther Parties arose throughout the country.

Speech at University of California, Berkeley

Flyer for “Black Power and Change” conference rally UC Berkeley, October, 1966

Due to the mass mobilizations by the civil rights movement and the Black rebellions in the inner cities, by 1968 legal segregation, Jim Crow, was destroyed. Blacks acquired the right to vote and access to jobs through affirmative action programs, to make up for the past discriminations. There was hope for a better life in the Black Community. However, after Martin Luther King, struggled against de facto segregation in Chicago, he realized that the struggle for economic equality was a more difficult fight than the struggle against Jim Crow. At this point he began to take similar anti-capitalist positions as Malcolm X.

Both Malcolm X and Martin Luther King opposed the Vietnam War prior to their assassinations. At the time of their assassinations, both Martin Luther King and Malcolm X were embarking on a course in opposition to the capitalist system. It is clear from reading and listening to their final speeches that they had both evolved to similar conclusions of capitalism’s role in the maintenance of racism. That is why they were assassinated. (For more information read The Assassinations of Martin Luther King, Jr. and Malcolm X.

It’s now known that during the rise of the modern civil rights movement, the government, led by Attorney General Robert F Kennedy, was spying on the movement and its leadership. In the 1970’s, the “Cointelpro” disruption operations by the government against the civil rights movement, the antiwar movement, and radicals and socialists, during that period, also became public knowledge. Under “Cointelpro” the different United States spy agencies used informers, agents, and agent provocateurs to disrupt organizations. One purpose of this program was to “neutralize” Malcolm X, Martin Luther King, and Elijah Muhammad,” in order to prevent the development of a “Black Messiah,” who would have the potential of uniting and leading a mass organization of Black Americans in their quest for freedom and economic equality.

IN 1967, King clearly wrote his outlook for the struggle to gain economic equality:

On Page 602, A Testament of Hope: the essential writings and speeches of Martin Luther: Martin Luther King stated the course that he was planning to take in the fight for economic equality:

. . . The Emergence of social initiatives by a revitalized labor movement would be taking place as Negros are placing economic issues on the highest agenda. The coalition of an energized section of labor, Negroes, unemployed, and welfare recipients may be the source of power that reshapes economic relationships and ushers in a breakthrough to a new level of social reform.. . . He continues on Page 631: There is nothing except shortsightedness to prevent us from guaranteeing an annual minimum — and livable — income for every American family. There is nothing but a lack of social vision to prevent us from paying an adequate wage to every American citizen whether he be a hospital worker, laundry worker, maid, or day laborer. There is nothing, except a tragic death wish, to prevent us from reordering our priorities, so that the pursuit of peaces will take precedence over the pursuit of war. There is nothing to keep us from remolding a recalcitrant status quo with bruised hands until we have fashioned it into a true brotherhood. . .

At that time, the stock market was below 1,000 points. Today, it is above 10,000 points, and yet there still is no social vision for paying an adequate wage and the real ƒabminimum wage has dropped 42% since 1968.

A last chance at rebuilding the movement was the first National Black Political Assembly on March 10,1972. “an estimated 10,000 Black people converged on a small steel town in Indiana for one of the greatest gatherings in the history of Africans in America – the Gary National Black Political Convention,” which was more commonly known as the ‘Gary Convention.’ A sea of Black faces chanted, ‘It’s Nation Time! It’s Nation Time!’ No one in the room had ever seen anything like this before. The radical Black nationalists clearly won the day; moderates who supported integration and backed the Democratic Party were in the minority. It gave birth to the “Gary Declaration” which stated:

. . . A Black political convention, indeed all truly Black politics, must begin from this truth: The American system does not work for the masses of our people, and it cannot be made to work without radical, fundamental changes. The challenge is thrown to us here in Gary. It is the challenge to consolidate and organize our own Black role as the vanguard in the struggle for a new society. To accept the challenge is to move to independent Black politics. There can be no equivocation on that issue. History leaves us no other choice. White politics has not and cannot bring the changes we need.8

Unfortunately, Black Democratic Party supporters such as Richard Hatcher the mayor of Gary Indiana, Jesse Jackson, Ron Daniels, and even Amiri Baraka betrayed the hope from the Cary Convention. Instead of the course that was decided at the convention, they led the way to support Black politicians and through them, the Democratic Party. “Vote for Me and I’ll set you Free” became the slogan for the day and the civil rights movement became completely demobilized and with its “leaders co-opted” into the system. From this demobilization, came the betrayal and atomization of the movement.

As Malcolm X said in his New York City speech, Dec. 1, 1963: … “The Negro revolution is controlled by foxy white liberals, by the Government itself….”

At first, there was an illusion of progress; there was a rise in the number on Black politicians. There was an increase in jobs for black professionals in government, in industry, and on television. There was an impression that things were getting better through the strategy of relying upon the Democratic Party to politically secure, protect, and advance the struggle for racial equality.

An example of what was wrong with this strategy was clearly demonstrated when Maynard Jackson was elected mayor of Atlanta Ga., in 1974.

At the time of Martin Luther King’s assassination, he was willing to risk jail and to organize a mass demonstration, in defiance of a court injunction and National Guardsmen, in armored personnel carriers equipped with 50-caliber machine guns, to help the striking Memphis municipal garbage workers. These workers ultimately won their union contract, and thousands of ordinary working families in that city got living wages that allowed them to educate their children, buy houses, live decent and dignified lives, and even retire.

In his last speech, he stated:

From Martin Luther King’s Last Speech, April 3, 1968, I’ve Been to The Mountaintop:

Now about injunctions: We have an injunction and we’re going into court tomorrow morning to fight this illegal, unconstitutional injunction. All we say to America is, “Be true to what you said on paper.” If I lived in China or even Russia, or any totalitarian country, MAYBE I COULD UNDERSTAND SOME OF THESE ILLEGAL INJUNCTIONS. Maybe I could understand the denial of certain basic First Amendment privileges, because they HAVEN’T committed themselves to that over there. But somewhere I read of the freedom of assembly. Somewhere I read of the freedom of speech. Somewhere I read of the freedom of the press. Somewhere I read that the greatness of America is the right to protest for RIGHTS. And so just as I say, WE AREN’T GOING TO LET ANY DOGS OR WATER HOSES TURN US AROUND, we aren’t going to let any injunction turn us around.

In contrast, Maynard Jackson quickly demonstrated that he was not beholden to or a leader of the Black population that elected him, but beholden to those who financed his election campaign and who helped his personal political and financial advancement. In Atlanta, Jackson, instead of helping city sanitation workers, fired more than a thousand city employees to crush their strike. In this, he had the support of white business leaders and the Atlanta Journal-Constitution. This contrast was clearly stated in the essay A disgrace before God: Striking black sanitation workers vs. black officialdom in 1977 Atlanta:

Memphis in 1968 best demonstrated this connection, where wildcat strikes by an all-black workforce against overtly racist city officials became a larger battle for black liberation and community self-management. This struggle eventually saw the involvement of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and other civil rights establishment figures. When Dr. King was assassinated the day after giving a stirring speech to assembled sanitation workers, victory for striking workers followed shortly for much of American liberal official society sympathized with the strikers against the racist city officials. The city recognized the strikers’ call for union recognition, nationally backed by the American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees (AFSCME) and conceded to demands for better pay and improved workplace conditions. This scene repeated itself in St. Petersburg and Cleveland later that year. This also occurred in Atlanta in 1970, where civil rights figures, some of whom were newly elected city officials, supported striking sanitation workers threatened with termination by Atlanta’s white mayor Sam Massell. Fast-forward seven years to the Atlanta of 1977 and something strange, one may think, happened. The script was flipped. The same black officials who supported sanitation workers against firings by a white mayor decided to replace striking city sanitation employees with scabs. This occurred with the full support of many old guard civil rights leaders and organizations, allied with business and civic groups associated with Atlanta’s white power structure during Jim Crow segregation. What explains the apparent about-face by black officials? The Atlanta strike of 1977 shows the coming of age of a coalition of black and white city officials, along with civic and business elites, under the leadership of the city’s first black mayor, Maynard Jackson. Just seven years earlier Jackson publicly sided with sanitation workers against a white mayor seeking to fire them. Jackson and some members of the civil rights establishment, in positions of local government by the mid 1970s, did not hesitate to marshal the forces of official society against the self-activity of black workers. They allied with white business and civic elites, the same people that just a few years earlier openly supported white supremacist segregation, all in the name of smashing the sanitation workers’ strike by any means necessary. This showed the open class hatred of black and white elites against working people, a prominent feature of communities in Atlanta for generations.

Similar ‘fruits’, from the political policy of supporting the “lesser evil” Democratic Party, has led to a set back for the struggle for civil rights and equality.

“Lesser evil” always means “More Evil”— the Republican Richard Nixon, the “greater evil” in 1968, would be the “lesser evil” to the Democrat Clinton (Bill and Hillary) in today’s world!

No longer fearing a mass civil rights movement in the streets, the Democrats have, for the past 30 years, shared responsibility for the gradual reduction of affirmative action and the victories of the movement.

From my own experience, the only way to enforce affirmative action, is if there are quotas for employment in the workplace. The new Black politicians, along with Jessie Jackson, came out against quotas in the 80s, helping to make affirmative action more difficult. Various court decisions helped to reduce the effects of affirmative action and to resegregate the nation’s school system. In 1995, President Clinton, as the leader of the Democratic Party, drafted a memorandum for the elimination of any program that creates (1) a quota; (2) preferences for unqualified individuals; (3) creates reverse discrimination (The slogan of the racists); or continues affirmative action even after its equal opportunity purposes have been achieved.” (A myth) Actually, according to a recent article from the Boston Globe, at the elite colleges, there is affirmative action for rich dim white kids.

The Democratic Party was responsible for the 1986 Anti-Drug Abuse Act which established a 100-to-1 sentencing ratio between possession of crack (mainly used in the inter-cities) and of cocaine powder (mainly used in the suburbs). Under this law, possession of five grams of crack is a felony and carries a mandated minimum five-year federal prison sentence. For cocaine powder it is only a misdemeanor for the possession of less than 500 grams of cocaine powder. The five-year felony sentence applies if one has 500 grams in their possession. This sentencing disproportion was based on phony testimony that crack was 50 times more addictive than powdered coke. The Democratic Party-controlled Congress then doubled this ratio as a so-called “violence penalty”.

This has led to “affirmative action” in the prison system, where Black inmates are a far greater in percentage of all prisoners than their percentage in the nation. At the same time, many states are now preventing those convicted of a felony from voting.

According to the Harvard Civil Rights Project, which recently was forced to move to UCLA, the public schools have become more separate and unequal— the consequences of the last two decades of resegregation along economic, ethnic and racist lines.

Throughout this land, both the Republican and Democratic Parties are gentrifying the inner cities, in the service of big business, and the poor are being scattered to the winds. It is how the rich are handling unemployment and poverty in this country. Recently, Black U.S. Senator Barack Obama (D-IL) went to Africa to publicize the catastrophe of Aids in Africa. He should have also gone to the Black Communities in the United States and publicized the crisis of Aids in Black America, where nearly half of the million Americans, who are living with HIV today, are Black. If fsct, it has become a Black America Disease!

The bipartisan corporate “bankruptcy reforms” in the late 80s to the present have allowed corporations to lay off workers, rob pension plans, and tear up union contracts. Because Black workers are still the “last hired and first fired”, they have received the brunt of these attacks.

Overall, the rich have become richer, and the poor have become poorer.

Ben H. Bagdikian put it well in his “Preface to the Sixth Edition” of the The Media Monopoly, after he explained that just six of the world’s largest corporations, control 90% of the mass media, he wrote:

The American economy [has been] undergoing an astonishing phenomenon that the mainstream news left largely unreported or actually glamorized in its infrequent references, the largest transfer of the national wealth in American history from a majority of the population to a small percentage of the country’s wealthiest families.

This process was facilitated by the fact that almost every “tax reform” from Kennedy in 1961, to Bush in 2004, has resulted in the taking of wealth from the working class and giving it to the capitalist class.

And yet, the Congressional Black Caucus echoes the “hype” from the government, the press, and the Republican and Democratic Parties, that things are better today. The economic figures from the bipartisan wage-price freeze in 1972 to today demonstrate that this it is false illusion. he Congressional Black Caucus echoes the “hype” from the government, the press, and the Republican and Democratic Parties, that things are better today. And yet, racism continues to be an institutional part of the United States.

According to infoplease, Black households median income in 1972 was $21,311 or $97,201.78 in 2005 dollars, while white Households median income in 1972 was $36,510 or $166,526.06 in 2005 dollars. In 2004 Black households had a median income in 2004 was $30,947 in 2005 dollars. White Households had the highest median income at $47,957 in 2005 dollars. Significantly lower than the median incomes for 1972.

These figures show that Black Households median income in 1972 was 58% of white households median income and approximate 64% of white households today. This does not represent progress, it represents that income for workers, Black People and other minorities has decreased since 1972. Black people now have an income of 64% of white households that has not kept up with inflation and has actually decreased by over 50% since 1972. Since the working class and the poor have been suffering an ever-increasing rate of taxation and concurrent cuts in government services, the decline in real wages and their standard of living has been worse.

In order to regain what has been lost and win equality rights for all, we must stop supporting those who are oppressing us – the Democratic and Republican Parties – and go back to what made all movements powerful. Which was relying upon ourselves and building our own independent power.

In his book, Where do we go from here: Chaos or community?, New York: Harper & Row, 1967, King wrote the course that he was planning to take in the fight for economic equality:

There is nothing, except a tragic death wish, to prevent us from reordering our priorities… The coalition of an energized section of labor, Negroes, unemployed, and welfare recipients may be the source of power that reshapes economic relationships and ushers in a breakthrough to a new level of social reform. . . . The total elimination of poverty, now a practical responsibility, the reality of equality in race relations and other profound structural changes in society may well begin here.”

. . .In 1968, having won landmark civil rights legislation, King strenuously urged racial justice advocates to shift from a civil rights to a human rights paradigm. A human rights approach, he believed, would offer far greater hope than the civil rights model had provided for those determined to create a thriving, multiracial democracy free from racial hierarchy. It would offer a positive vision of what we can strive for-a society in which people of all races are treated with dignity and have the right to food, shelter, health care, education, and security.“We must see the great distinction between a reform movement and a revolutionary movement,” he said. “We are called upon to raise certain basic questions about the whole society. The Poor People’s Movement seemed poised to unite poor people of all colors in a bold challenge to the prevailing economic and political system. . . . — Michelle Alexander, Think Outside the Bars Why real justice means fewer prisons.

Such a coalition, as King envisioned it thirty-three years ago, is needed today.

In order to survive, we must begin the begin.

For a graphic video on how race relations have not changed in this country watch and listen to Michelle Alexander, the writer of New Jim Crow, March 17, 2011 video.

From Chapter 5, The New Jim Crow: Obama—the Promise and the Peril : By Michelle Alexander

So what is to be demanded in this moment in our nation’s racial history? If the answer is more power, more top jobs, more slots in fancy schools for “us”—a narrow, racially defined us that excludes many—we will continue the same power struggles and can expect to achieve many of the same results. Yes, we may still manage to persuade mainstream voters in the midst of an economic crisis that we have relied too heavily on incarceration, that prisons are too expensive, and that drug use is a public health problem, not a crime.

But if the movement that emerges to end mass incarceration does not meaningfully address the racial divisions and resentments that gave rise to mass incarceration, and if it fails to cultivate an ethic of genuine care, compassion, and concern for every human being—of every class, race, and nationality — within our nation’s borders, including poor whites, who are often pitted against poor people of color, the collapse of mass incarceration will not mean the death of racial caste in America.

Inevitably a new system of racialized social control will emerge—one that we cannot foresee, just as the current system of mass incarceration was not predicted by anyone thirty years ago. No task is more urgent for racial justice advocates today than ensuring that America’s current racial caste system is its last.

Given what is at stake at this moment in history, bolder, more inspired action is required than we have seen to date. Piecemeal, top-down policy reform on criminal justice issues, combined with a racial justice discourse that revolves largely around the meaning of Barack Obama’s election and “post-racialism,” will not get us out of our nation’s racial quagmire. We must flip the script. Taking our cue from the courageous civil rights advocates who brazenly refused to defend themselves, marching unarmed past white mobs that threatened to kill them, we, too, must be the change we hope to create. If we want to do more than just end mass incarceration — if we want to put an end to the history of racial caste in America — we must lay down our racial bribes, join hands with people of all colors who are not content to wait for change to trickle down, and say to those who would stand in our way: Accept all of us or none.

That is the basic message that Martin Luther King Jr. aimed to deliver through the Poor People’s Movement back in 1968. He argued then that the time had come for racial justice advocates to shift from a civil rights to a human rights paradigm, and that the real work of movement building had only just begun. 61

A human rights approach, he believed, would offer far greater hope for those of us determined to create a thriving, multiracial, multiethnic democracy free from racial hierarchy than the civil rights model had provided to date. It would offer a positive vision of what we can strive for — a society in which all human beings of all races are treated with dignity, and have the right to food, shelter, health care, education, and security. 62

This expansive vision could open the door to meaningful alliances between poor and working-class people of all colors, who could begin to see their interests as aligned, rather than in conflict—no longer in competition for scarce resources in a zero-sum game.

A human rights movement, King believed, held revolutionary potential. Speaking at a Southern Christian Leadership Conference staff retreat in May 1967, he told SCLC staff, who were concerned that the Civil Rights Movement had lost its steam and its direction, “It is necessary for us to realize that we have moved from the era of civil rights to the era of human rights.” Political reform efforts were no longer adequate to the task at hand, he said. “For the last 12 years, we have been in a reform movement…. [But] after Selma and the voting rights bill, we moved into a new era, which must be an era of revolution. We must see the great distinction between a reform movement and a revolutionary movement. We are called upon to raise certain basic questions about the whole society.” 63

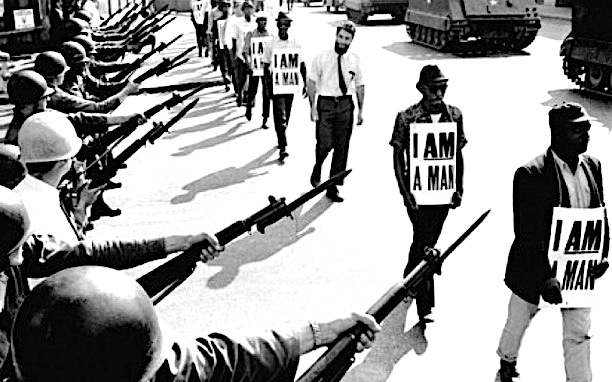

More than forty years later, civil rights advocacy is stuck in a model of advocacy King was determined to leave behind. Rather than challenging the basic structure of society and doing the hard work of movement building —the work to which King was still committed at the end of his life — we have been tempted too often by the opportunity for people of color to be included within the political and economic structure as-is, even if it means alienating those who are necessary allies. We have allowed ourselves to be willfully blind to the emergence of a new caste system—a system of social excommunication that has denied millions of African Americans basic human dignity. The significance of this cannot be overstated, for the failure to acknowledge the humanity and dignity of all persons has lurked at the root of every racial caste system. This common thread explains why, in the 1780s, the British Society for the Abolition of Slavery adopted as its official seal a woodcut of a kneeling slave above a banner that read, “AM I NOT A MAN AND A BROTHER?” That symbol was followed more than a hundred years later by signs worn around the necks of black sanitation workers during the Poor People’s Campaign answering the slave’s question with the simple statement, I AM A MAN.

The fact that black men could wear the same sign today in protest of the new caste system suggests that the model of civil rights advocacy that has been employed for the past several decades is, as King predicted, inadequate to the task at hand. If we can agree that what is needed now, at this critical juncture, is not more tinkering or tokenism, but as King insisted forty years ago, a “radical restructuring of our society,” then perhaps we can also agree that a radical restructuring of our approach to racial justice advocacy is in order as well.

All of this is easier said than done, of course. Change in civil rights organizations, like change in society as a whole, will not come easy. Fully committing to a vision of racial justice that includes grassroots, bottom-up advocacy on behalf of “all of us” will require a major reconsideration of priorities, staffing, strategies, and messages. Egos, competing agendas, career goals, and inertia may get in the way. It may be that traditional civil rights organizations simply cannot, or will not, change. To this it can only be said, without a hint of disrespect: adapt or die.

If Martin Luther King Jr. is right that the arc of history is long, but it bends toward justice, a new movement will arise; and if civil rights organizations fail to keep up with the times, they will pushed to the side as another generation of advocates comes to the fore.

Hopefully the new generation will be led by those who know best the brutality of the new caste system — a group with greater vision, courage, and determination than the old guard can muster, trapped as they may be in an outdated paradigm. This new generation of activists should not disrespect their elders or disparage their contributions or achievements; to the contrary, they should bow their heads in respect, for their forerunners have expended untold hours and made great sacrifices in an elusive quest for justice. But once respects have been paid, they should march right past them, emboldened, as King once said, by the fierce urgency of now.

Those of us who hope to be their allies should not be surprised, if and when this day comes, that when those who have been locked up and locked out finally have the chance to speak and truly be heard, what we hear is rage. The rage may frighten us; it may remind us of riots, uprisings, and buildings aflame. We may be tempted to control it, or douse it with buckets of doubt, dismay, and disbelief. But we should do no such thing. Instead, when a young man who was born in the ghetto and who knows little of life beyond the walls of his prison cell and the invisible cage that has become his life, turns to us in bewilderment and rage, we should do nothing more than look him in the eye and tell him the truth. We should tell him the same truth the great African American writer James Baldwin told his nephew in a letter published in 1962, in one of the most extraordinary books ever written, and searing conviction, Baldwin had this to say to his young nephew:

This is the crime of which I accuse my country and my countrymen, and for which neither I nor time nor history will ever forgive them, that they have destroyed and are destroying hundreds of thousands of lives and do not know it and do not want to know it…. It is their innocence which constitutes the crime…. This innocent country set you down in a ghetto in which, in fact, it intended that you should perish. The limits of your ambition were, thus, expected to be set forever. You were born into a society which spelled out with brutal clarity, and in as many ways as possible, that you were a worthless human being. You were not expected to aspire to excellence: you were expected to make peace with mediocrity…. You have, and many of us have, defeated this intention; and, by a terrible law, a terrible paradox, those innocents who believed that your imprisonment made them This is the crime of which I accuse my country and my countrymen, and for which neither I nor time nor history will ever forgive them, that they have destroyed and are destroying hundreds of thousands of lives and do not know it and do not want to know it…. It is their innocence which constitutes the crime…. This innocent country set you down in a ghetto in which, in fact, it intended that you should perish. The limits of your ambition were, thus, expected to be set forever. You were born into a society which spelled out with brutal clarity, and in as many ways as possible, that you were a worthless human being. You were not expected to aspire to excellence: you were expected to make peace with mediocrity…. You have, and many of us have, defeated this intention; and, by a terrible law, a terrible paradox, those innocents who believed that your imprisonment made them safe are losing their grasp on reality. But these men are your brothers — your lost, younger brothers. And if the word integration means anything, this is what it means: that we, with love, shall force our brothers to see themselves as they are, to cease fleeing from reality and begin to change it. For this is your home, my friend, do not be driven from it; great men have done great things here, and will again, and we can make America what it must become. It will be hard, but you come from sturdy, peasant stock, men who picked cotton and dammed rivers and built railroads, and, in the teeth of the most terrifying odds, achieved an unassailable and monumental dignity. You come from a long line of great poets since Homer. One of them said, The very time I thought I was lost, My dungeon shook and my chains fell off…. We cannot be free until they are free. God bless you, and Godspeed.

The Memphis Sanitation Worker Strike, 1968 Photo: Ernest Withers, civil rights photographer

When a people are mired in oppression, they realize deliverance only when they have accumulated the power to enforce change. The powerful never lose opportunities — they remain available to them. They powerless, on the other hand, never experience opportunity — it is always arriving at a later time.

The nettlesome task of Negroes today is to discover how to organize our strength into compelling power so that government cannot elude our demands. We must develop, from strength, a situation in which the government finds it wise and prudent to collaborate with us. It would be the height of naiveté to wait passively until the administration had somehow been infused with such blessings of good will that it implored us for our programs.

We must frankly acknowledge that in past years our creativity and imagination were not employed in learning how to develop power. We found a method in nonviolent protest that worked, and we employed it enthusiastically. We did not have leisure to probe for a deeper understanding of its laws and lines of development. Although our actions were bold and crowned with successes, they were substantially improvised and spontaneous. They attained the goals set for them but carried the blemishes of our inexperience.

This is where the civil rights movement stands today. Now we must take the next major step of examining the levers of power which Negroes must grasp to influence the course of events.

In our society power sources can always finally be traced to ideological, economic and political forces.

In the area of ideology, despite the impact of the works of a few Negro writers on a limited number of white intellectuals, all too few Negro thinkers have exerted an influence on the main currents of American thought. Nevertheless, Negroes have illuminated imperfections in the democratic structure that were formerly only dimly perceived, and have forced a concerned reexamination of the true meaning of American democracy. As a consequence of the vigorous Negro protest, the whole nation has for a decade probed more searchingly the essential nature of democracy, both economic and political. By taking to the streets and there giving practical lessons in democracy and its defaults, Negroes have decisively influenced white thought.

Lacking sufficient access to television, publications and broad forums, Negroes have had to write their most persuasive essays with the blunt pen of marching ranks. The many white political leaders and well-meaning friends who ask Negro leadership to leave the streets may not realize that they are asking us effectively to silence ourselves. More white people learned more about the shame of America, and finally faced some aspects of it, during the years of nonviolent protest than during the century before. Nonviolent direct action will continue to be a significant source of power until it is made irrelevant by the presence of justice.

The economic highway to power has few entry lanes for Negroes. Nothing so vividly reveals the crushing impact of discrimination and the heritage of exclusion as the limited dimensions of Negro business in the most powerful economy in the world. America’s industrial production is half of the world’s total, and within it the production of Negro business is so small that it can scarcely be measured on any definable scale.

Yet in relation to the Negro community the value of Negro business should not be underestimated. In the internal life of the Negro society it provides a degree of stability. Despite formidable obstacles it has developed a corps of men of competence and organizational discipline who constitute a talented leadership reserve, who furnish inspiration and who are a resource for the development of programs and planning. They are a strength among the weak though they are weak among the mighty.

There exist two other areas, however, where Negroes can exert substantial influence on the broader economy. As employees and consumers, Negro numbers and their strategic disposition endow them with a certain bargaining strength.

Within the ranks of organized labor there are nearly two million Negroes, and they are concentrated in key industries. In the truck transportation, steel, auto and food industries, which are the backbone of the nation’s economic life, Negroes make up nearly twenty percent of the organized work force, although they are only ten percent of the general population. This potential strength is magnified further by the fact of their unity with millions of white workers in these occupations. As co-workers there is a basic community of interest that transcends many of the ugly divisive elements of traditional prejudice. There are undeniably points of friction, for example, in certain housing and education questions. But the severity of the abrasions is minimized by the more commanding need for cohesion in union organizations.

The union record in relation to Negro workers is exceedingly uneven, but potential for influencing union decisions still exists. In many of the larger unions the white leadership contains some men of ideals and many more who are pragmatists. Both groups find they are benefited by a constructive relationship to their Negro membership. For those compelling reasons, Negroes, who are almost wholly a working people, cannot be casual toward the union movement. This is true even though some unions remain uncontestably hostile.

In days to come, organized labor will increase its importance in the destinies of Negroes. Negroes pressed into the proliferating service occupations-traditionally unorganized and with low wages and long hours-need union protection, and the union movement needs their membership to maintain its relative strength in the whole society. On this new frontier Negroes may well become the pioneers that they were in the early organizing days of the thirties.

To play our role fully as Negroes we will also have to strive for enhanced representation and influence in the labor movement. Our young people need to think of union careers as earnestly as they do of business careers and professions. They could do worse than emulate A. Phillip Randolph, who rose to the executive council of the AFL-CIO and became a symbol of the courage, compassion and integrity of an enlightened labor leader.

Indeed, the question may be asked why we have produced only one Randolph in nearly half a century. Discrimination is not the whole answer. We allowed ourselves to accept middle-class prejudices against the labor movement. Yet this is one of those fields in which higher education is not a requirement for high office. In shunning it, we have lost an opportunity. Let us try to regain it now, at a time when the joint forces of Negroes and labor may be facing a historic task of social reform.

The other economic leader available to the Negro is as a consumer. The Southern Christian Leadership Council has pioneered in developing mass boycott movements in a frontal attack on discrimination. In Birmingham it was not the marching alone that brought about integration of public facilities in 1963. The downtown business establishments suffered for weeks under our almost unbelievably effective boycott. The significant percentage of their sales that vanished, the ninety-eight percent of their Negro customers who stayed home, educated them forcefully to the dignity of the Negro as a consumer.

Later we crystallized our experiences in Birmingham and elsewhere and developed a department in SCLC called Operation Breadbasket. This has as its primary aim the securing of more and better jobs for the Negro people. It calls on the Negro community to support those businesses that will give a fair share of jobs to Negroes and to withdraw its support from those businesses that have discriminatory policies.

Operation Breadbasket is carried out mainly by clergymen. First, a team of ministers calls on the management of a business in the community to request basic facts on the company’s total number of employees, the number of Negro employees, the departments or job classifications in which all employees are located, and the salary ranges for each category. The team then returns to the steering committee to evaluate the data and to make a recommendation concerning the number of new and upgraded jobs that should be requested. Then the team transmits the request to the management to hire or upgrade a specified number of “qualifiable” Negroes within a reasonable step of real power and pressure is taken: a massive call for economic withdrawal from the company’s product and accompanying demonstrations if necessary.

At present SCLC has Operation Breadbasket functioning in some twelve cities, and the results have been remarkable. In Atlanta, for instance, the Negroes’ earning power has been increased by more than twenty million dollars annually over the past three years through a carefully disciplined program of selective buying and negotiation by the Negro ministers. During the last eight months in Chicago, Operation Breadbasket successfully completed negotiations with three major industries: milk, soft drinks and chain grocery stores. Four of the companies involved concluded reasonable agreements only after short “don’t buy” campaigns. Seven other companies were able to make the requested changes across the conference table, without necessitating a boycott. Two other companies, after providing their employment information to the ministers, were sent letters of commendation for their healthy equal-employment practices. The net results add up to approximately eight hundred new and upgraded jobs for Negro employees, worth a little over seven million dollars in new annual income for Negro families. In Chicago we have recently added a new dimension to Operation Breadbasket. Along with requesting new job opportunities, we are now requesting that businesses with stores in the ghetto deposit the income for those establishments in Negro-owned banks, and that Negro-owned products be placed on the counters of all their stores. In this way we seek to stop the drain of resources out of the ghetto with nothing remaining there for its rehabilitation.

The final major area of untapped power for the Negro is the political arena. Higher Negro birth rates and increasing Negro migration, along with the exodus of the white population to the suburbs, are producing the fast-gathering Negro majorities in the large cities. This changing composition of the cities has political significance. Particularly in the North, the large cities substantially determine the political destiny of the state. These states, in turn, hold the dominating electoral votes in presidential contests. The future of the Democratic Party, which rests so heavily on its coalition of urban minorities, cannot be assessed without taking into account which way the Negro vote turns. The wistful hopes of the Republican Party for large-city influence will also be decided not in the boardrooms of great corporations but in the teeming ghettos.

The growing Negro vote in the South is another source of power. As it weakens and enfeebles the dixiecrats, by concentrating its blows against them, it undermines the congressional coalition of southern reactionaries and their northern Republican colleagues. That coalition, which has always exercised a disproportionate power in Congress by controlling its major committees, will lose its ability to frustrate measures of social advancement and to impose its perverted definition of democracy on the political thought of the nation.

The Negro vote at present is only a partially realized strength. It can still be doubled in the South. In the North even where Negroes are registered in equal proportion to whites, they do not vote in the same proportions. Assailed by a sense of futility, Negroes resist participating in empty ritual. However, when the Negro citizen learns that united and organized pressure can achieve measurable results, he will make his influence felt. Out of this conscious act, the political power of the aroused minority will be enhanced and consolidated.

We have many assets to facilitate organization. Negroes are almost instinctively cohesive. We band together readily, and against white hostility we have an intense and wholesome loyalty to each other. We are acutely conscious of the need, and sharply sensitive to the importance, of defending our own. Solidarity is a reality in Negro life, as it always has been among the oppressed.

On the other hand, Negroes are capable of becoming competitive, carping and, in an expression of self-hate, suspicious and intolerant of each other. A glaring weakness in Negro life is lack of sufficient mutual confidence and trust.

Negro leaders suffer from this interplay of solidarity and divisiveness, being either exalted excessively or grossly abused. Some of these leaders suffer from an aloofness and absence of faith in their people. The white establishment is skilled in flattering and cultivating emerging leaders. It presses its own image on them and finally, from imitation of manners, dress and style of living, a deeper strain of corruption develops. This kind of Negro leader acquires the white man’s contempMadox white than he is among his own people. His language changes, his location changes, his income changes, and ultimately he changes from the representative of the Negro to the white man into the white man’s representative of the Negro. The tragedy is that too often he does not recognize what has happened to him.

I learned a lesson many years ago from a report of two men who flew to Atlanta to confer with a Negro civil rights leader at the airport. Before they could begin to talk, the porter sweeping the floor drew the local leader aside to talk about a matter that troubled him. After fifteen minutes has passed, one of the visitors said bitterly to his companion, “I am just too busy for this kind of nonsense. I haven’t come a thousand miles to sit and wait while he talks to a porter.”

The other replied “When the day comes that he stops having time to talk to a porter, on that day I will not have the time to come one mile to see him.”

We need organizations that are permeated with mutual trust, incorruptibility and militancy. Without this spirit we may have numbers but they will add up to zero. We need organizations that are responsible, efficient and alert. We lack experience because ours is a history of disorganization. But we will prevail because our need for progress is stronger than the ignorance force upon us. If we realize how indispensable is responsible militant organization to our struggle, we will create it as we managed to crate underground railroads, protest groups, self-help societies and the churches that have always been our refuge, our source of hope and our source of action.

Negroes have been slow to organize because they have been traditionally manipulated. The political powers take advantage of three major weaknesses: the manner in which our political leaders emerge; our failure so far to achieve effective political alliances; and the Negro’s general reluctances to participate fully in political life.

The majority of Negro political leaders do not ascend to prominence on the shoulders of mass support. Although genuinely popular leaders are now emerging, most are still selected by white leadership, elevated to position, supplied with resources and inevitably subjected to white control. The mass of Negroes nurtures a healthy suspicion toward this manufactured leader, who spends little time in persuading them that he embodies personal integrity, commitment and ability and offers few programs and less service. Tragically, he is in too many respects not a fighter for a new life but a figurehead of the old one. Hence, very few Negro political leaders are impressive or illustrious to their constituents. They enjoy only limited loyalty and qualified support.

This relationship in turn hampers the Negro leader in bargaining with genuine strength and independent firmness with white party leaders. The whites are all too well aware of his impotence and his remoteness from his constituents, and they deal with him as a powerless subordinate. He is accorded a measure of dignity and personal respect but not political power.

The Negro politician therefore fines himself in a vacuum. He has no base in either direction on which to build influence and attain leverage.

In two national polls among Negroes to name their most respected leaders, out of the highest fifteen, only a single politician figure, Congressman Adam Clayton Powell, was included and he was in the lower half of both lists. This is in marked contrast to polls in which white people choose their most popular leaders; political personalities are always high on the lists and are represented in goodly numbers. There is no Negro personality evoking affection, respect and emulation to correspond to John F. Kennedy, Eleanor Roosevelt, Herbert Lehman, Earl Warren, and Adlai Stevenson, to name but a few.

The circumstances in which Congressman Powell emerged into leadership and the experiences of his career are unique. It would not shed light on the larger picture to attempt to study the very individual factors that apply to him. It is fair to say no other Negro political leader is similar, either in the strengths he possesses, the power he attained or the errors he has committed.

And so we shall have to create leaders who embody virtues we can respect, who have moral and ethical principles we can applaud with an enthusiasm that enables us to rally support for them based on confidence and trust. We will have to demand high standards and give consistent, loyal support to those who merit it. We will have to be a reliable constituency for those who merit it. We will have to be a reliable constituency for those who prove themselves to be committed political warriors in our behalf. When our movement has partisan political personalities whose unity with their people is unshakable and whose independence is genuine, they will be treated in white political councils with the respect those who embody such power deserve.

In addition to the development of genuinely independent and representative political leaders, we shall have to master the art of political alliances. Negroes should be natural allies of many white reform and independent political groups, yet they are more commonly organized by the old-line machine politicians. We will have to learn to refuse crumbs from the big-city machines and steadfastly demand a fair share of the loaf. When the machine politicians demur, we must be prepared to act in unity and throw our support to such independent parties or reform wings of the major parties as are prepared to take our demands seriously and fight for them vigorously.

The art of alliance politics is more complex and more intricate than it is generally pictured. It is easy to put exciting combinations on paper. It evokes happy memories to recall that our victories in the past decade were won with a broad collation of organizations representing a wide variety of interests. But we deceive ourselves if we envision the same combination backing structural changes in the society. It did not come together for such a program and will not reassemble for it.

A true alliance is based upon some self-interest of each component group and a common interest into which they merge. For an alliance to have permanence and loyal commitment from its various elements, each of them must have a goal from which it benefits and none must have an outlook in basic conflict with the others.

If we employ the principle of selectivity along these lines, we will find millions of allies who in serving themselves also support us, and on such sound foundations unity and mutual trust and tangible accomplishment will flourish.

In the changing conditions of the South, we will find alliances increasingly instrumental in political progress. For a number of years there were de facto alliances in some states in which Negroes voted to a moderate position, even though he did not articulate an appeal for Negro votes. In recent years the transformation has accelerated, and many white candidates have entered alliances publicly. As they perceived that the Negro vote was becoming a substantial and permanent factor, they could not remain aloof from it. More and more, competition will develop among white political forces for such a significant bloc of votes, and a monolithic white unity based on racism will no longer be possible.

Racism is a tenacious evil, but it is not immutable. Millions of underprivileged whites are in the process of considering the contradiction between segregation and economic progress. White supremacy can feed their egos but not their stomachs. They will not go hungry or forgo the affluent society to remain racially ascendant.

Governors Wallace and Maddox whose credentials as racists are impeccable, understand this, and for that reason they represent themselves as liberal populists as well. Temporarily they can carry water on both shoulders, but the ground is becoming unsteady beneath their feet. Each of them was faced in the primary last year with a new breed of white southerner who for the first time in history met with Negro organizations to solicit support and championed economic reform without racial demagogy. These new figures won significant numbers of white votes, insufficient for victory but sufficient to point the future directions of the South.

It is true that the Negro vote has not transformed the North; but the fact that northern alliances and political action generally have been poorly executed is no reason to predict that the negative experiences will be automatically extended in the North or duplicated in the South. The northern Negro has never used direct action on a mass scale for reforms, and anyone who predicted ten years ago that the southern Negro would also neglect it would have dramatically been proved in error.

Everything Negroes need will not like magic materialize from the use of the ballot. Yet as a lever of power, if it is given studious attention and employed with the creativity we have proved through our protest activities we possess, it will help to achieve many far-reaching changes during our lifetimes.

The final reason for our dearth of political strength, particularly in the North, arises from the grip of an old tradition on many individual Negroes. They tend to hold themselves aloof from politics as a serious concern. They sense that they are manipulated, and their defense is a cynical disinterest. To safeguard themselves on this front from the exploitation that torments them in so many areas, they shut the door to political activity and retreat into the dark shadows of passivity. Their sense of futility is deep and in terms of their bitter experiences it is justified. They cannot perceive political action as a source of power. It will take patient and persistent effort to eradicate this mood, but the new consciousness of strength developed in a decade of stirring agitation can be utilized to channel constructive Negro activity into political life and eliminate the stagnation produced by an outdated and defensive paralysis.

In the future we must become intensive political activists. We must be guided in this direction because we need political strength, more desperately than any other group in American society. Most of us are too poor to have adequate economic power, and many of us are too rejected by the culture to be part of any tradition of power. Necessity will draw us toward the power inherent in the creative uses of politics.

Negroes nurture a persisting myth that the Jews of America attained social mobility and status solely because they had money. It is unwise to ignore the error for many reasons. In a negative sense it encourages anti-Semitism and overestimates money as a value. In a positive sense, the full truth reveals a useful lesson.

Jews progressed because they possessed a tradition of education combined with social and political action. The Jewish family enthroned education and sacrificed to get it. The result was far more than abstract learning. Uniting social action with educational competences, Jews became enormously effective in political life. Those Jews who became lawyers, businessmen, writers, entertainers, union leaders and medical men did not vanish into the pursuits of their trade exclusively. They lived an active life in political circles, learning the techniques and arts of politics.

Nor was it only the rich who were involved in social and political action. Millions of Jews for half a century remained relatively poor, but they were far from passive in social and political areas. They lived in homes in which politics was a household word. They were deeply involved in radical parties, liberal parties, and conservative parties — they formed many of the. Very few Jews sank into despair and escapism even when discrimination assailed the spirit and corroded initiative. Their life raft in the sea of discouragement was social action.

Without overlooking the towering differences between the Negro and Jewish experiences, the lesson of Jewish mass involvement in social and political action and education is worthy of emulation. Negroes have already started on this road in creating the protest movement, but this is only a beginning. We must involve everyone we can reach, even those with inadequate education, and together acquire political sophistication by discussion, practice, and reading.

The many thousands of Negroes who have already found intellectual growth and spiritual fulfillment on this path know its creative possibilities. They are not among the legions of the lost, they are not crushed by the weight of centuries. Most heartening, among the young the spirit of challenge and determination for change is becoming an unquenchable force.

But the scope of struggle is still too narrow and too restricted. We must turn more of our energies and focus our creativity on the useful things that translate into power. We in this generation must do the work and in doing it stimulate our children to learn and acquire higher levels of skill and technique.

It must become a crusade so vital that civil rights organizers do not repeatedly have to make personal calls to summon support. There must be a climate of social pressure in the Negro community that scorns the Negro who will not pick up his citizenship rights and add his strength enthusiastically and voluntarily to the accumulation of power for himself and his people. The past years have blown fresh winds through ghetto stagnation, but we are on the threshold of a significant change that demands a hundredfold acceleration. By 1970 then of our larger cities will have Negro majorities if present trends continue. We can shrug off this opportunity or use it for a new vitality to deepen and enrich our family and community life.

We must utilize the community action groups and training centers no proliferating in some slum areas to crate not merely an electorate, but a conscious, alert and informed people who know their direction and whose collective wisdom and vitality commands respect. The slave heritage can be cast into the dim past by our consciousness of our strengths and a resolute determination to use them in our daily experiences.

Power is not the white man’s birthright; it will not be legislated for us and delivered in neat government packages. It is social force any group can utilize by accumulation its elements in a planned deliberate campaign to organized it under its own control.

Conclusion

Unlike Malcolm X, whose assassination cut short his organizing plans, King was organizing a movement to obtain his stated goals when he was assassinated. In fact, he was in Memphis to build that “coalition of an energized section of labor, Negroes, unemployed, and welfare recipients” in support of striking municipal sanitation workers.

If such a force had been launched, the whole power of the antiwar and civil rights movement in the 1960s could have transformed the labor movement and become “the source of power that reshapes economic relationships and ushers in a breakthrough to a new level of social reform.”

To combat the rise of the Civil Right Movement, the “war on poverty” was first launched in 1964 along with the concept of “Black Politicians”. Malcolm X described this process in his Jan. 7, 1965 speech The Prospects for Freedom, at the Militant Labor Forum, in New York City (For complete an audio of the speech go here.):

They have a new gimmick every year. They’re going to take one of their boys, black boys, and put him in the cabinet so he can walk around Washington with a cigar. Fire on one end and fool on the other end. And because his immediate personal problem will have been solved he will be the one to tell our people: ‘Look how much progress we’re making. I’m in Washington, D.C., I can have tea in the White House. I’m your spokesman, I’m your leader.’ While our people are still living in Harlem in the slums. Still receiving the worst form of education. But how many sitting here right now feel that they could [laughs] truly identify with a struggle that was designed to eliminate the basic causes that create the conditions that exist? Not very many. They can jive, but when it comes to identifying yourself with a struggle that is not endorsed by the power structure, that is not acceptable, that the ground rules are not laid down by the society in which you live, in which you are struggling against, you can’t identify with that, you step back. It’s easy to become a satellite today without even realizing it. This country can seduce God. Yes, it has that seductive power of economic dollarism. You can cut out colonialism, imperialism and all other kind of ism, but it’s hard for you to cut that dollarism. When they drop those dollars on you, you’ll fold though.

After the assassination of Martin Luther King and the subsequent rebellions in the inner cities protesting his assassination, the Democratic Party’s “war on poverty” started laying dollars on any potential Black leaders and grooming Black Candidates.

John Lewis, formally of SNCC, became enlightened, he ignored the Black Panthers and saw the Democratic Party, symbolized by a jackass, as his party. Most of what W.E. B. Dubois described as the “talented tenth” were bought off by this process. The more radical concepts that Martin Luther King and Malcolm X had developed at the time of their deaths disappeared from the scene. No one took up where they left off. The governmental policy, directed towards the ‘leaders’ of the civil rights movement, of the carrot (dollarism) and the stick (assassinations) had proven to be successful.

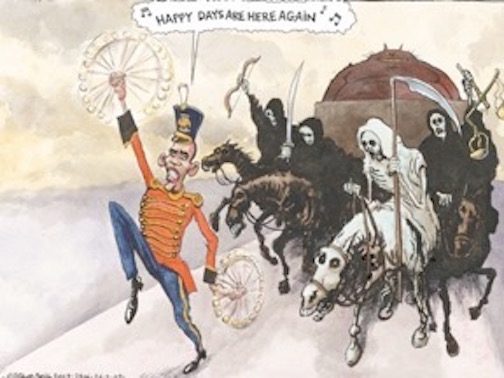

Due to the emergence of Barack Obama as a Presidential Candidate, in 2008, I feel the necessity to update this article.

In the last quarter of 2007 alone, Barack Obama and Hilary Clinton each raised about $25 million apiece. During the course of the primary election fight they will spend Hundreds of millions of dollars! In fact, they are on a record setting pace for total spent for Presidential elections. So far, “Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama place first and second place in terms of the most money raised (at $116 million and $102 million respectively). Republicans’ funds are less in comparison, with frontrunner John McCain raising $41 million, and Mitt Romney, Rudy Giuliani, and Mike Huckabee respectively at $88.5 million, $60.9 million, and $9 million.” — The Democratic Party and the Business of Elections Following the Money Trail

The capitalist ruling class is voting, with most of their money, for a Hilary/Barack “change” and a side bet on a McCain “change” to maintain the status quo. But there will be no change in how the government is run, whether Clinton, McCain, or Obama win the election. Does anyone seriously propose that Obama or Clinton will oppose the money and power that elected them? Or that Obama will remember where he came from when his is elected, even though he does not come from the Black Community in the United States?